Pantomime: The History and Metamorphosis of a Theatrical Ideology: Table of Contents

PDF version of the entire book.

Marcel Marceau

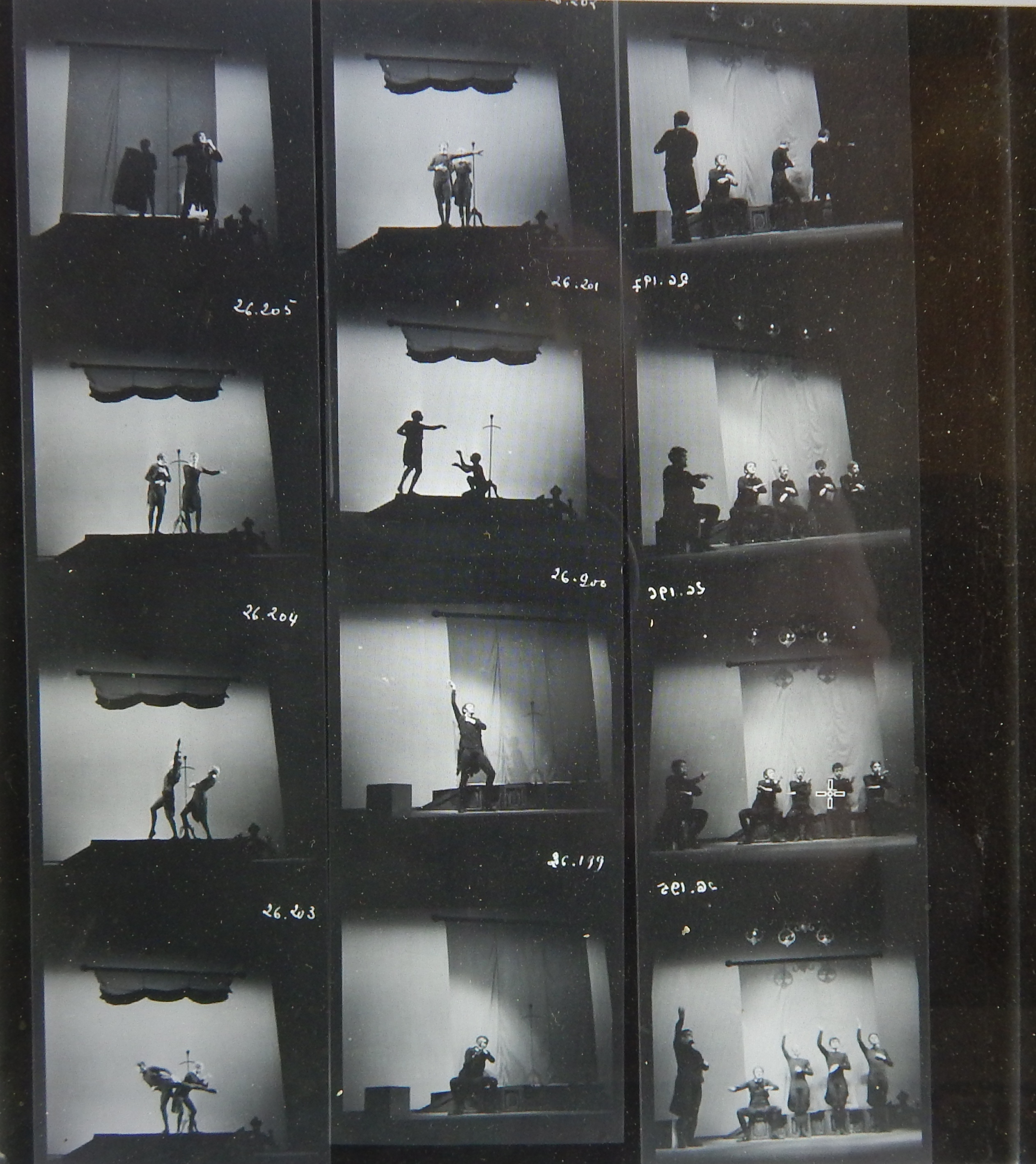

Yet the international spreading of mime school culture probably could not have happened without the enormously popular, commercial performances of Marcel Marceau (1923-2007), the most famous of all Decroux’s students. Marceau’s performances, many of which occurred on television, made the world aware of mime as a distinct genre of performance that justified motives for studying mime. Many of those who came to Paris to study mime in the 1960s and 1970s were residents of other countries; Leabhart says that most students in Decroux’s classes were foreigners (2003: 432). Marceau was born in Strasbourg. His parents were Jewish; he joined the Resistance in 1944, after the Nazis had murdered his father in Auschwitz. Though he spoke several languages, he developed an intense attachment to pantomimic performance while working for the Resistance, where he mimed the role of a scout leader while smuggling Jewish children to safety in Spain. He always regarded the silent films of Charlie Chaplin as the greatest influence in his life. In 1945, he enrolled in Dullin’s dramatic arts school, where he studied under Decroux. The following year, he appeared as Arlequin in Barrault’s production of Baptiste. This experience inspired him to produce his own “mimodrama” the same year, Praxitele et le poisson d’or, in which he introduced a prototype of the Bip character that became his lifelong performance persona. Marceau then appeared in 1947, at the tiny Théâtre de Poche, in a performance of several Bip sketches. The performance prompted Decroux to expel Marceau from the school, for Decroux felt that Marceau’s desire to entertain corrupted the goal of corporeal mime. However, Marceau’s goal was to produce more mimodramas in which Bip only occasionally appeared merely as one of several ensemble characters played by other actors. After presenting Bip in a rather somber mimodrama, Mort avant l’aube (1948), he formed (1949) a company to produce more mimodramas: Le Manteau (1951), an adaptation of the 1842 overcoat story by Gogol; Pierrot de Montmartre (1952), “inspired by the black Pierrot of Alphonse Willett”; Les Trois Perruques (1953), another comedy set in the 1840s; Loup de Tsu Ku Mi (1956), an archaic, Kabuki-like drama in an abstract Japanese setting; Paris qui rit, Paris qui pleure (1958), in which Marceau played a Parisian street newspaper vendor in what appear to be bygone days; Don Juan (1964), an adaptation of the 1630 play by Tirso de Molina (1579-1648). In all these works and others, Marceau collaborated with the actor Pierre Verry (1913-2009), also a former student of Decroux; and Etienne Bertrand Weil (1919-2001), who had photographed some of Decroux’s demonstrations, photographed Marceau’s productions, and later became notable for using multiple and time-lapse exposures to capture the movement of stage performers. While the narrative organization of action in Marceau’s mimodramas remains incomplete (he never published any scenarios), the photos of them show an investment in simple scenery and fairly complex period costumes, with the stage containing up to ten characters (Les Trois Perruques) [Figure 97]. Joseph Kosma was one of the composers who wrote music for the productions. All the productions, even Paris qui rit, Paris qui pleure, evoke a nineteenth century atmosphere. He also made a short film, Au Jardin (1954), shot in a studio with a rather elaborate set and accompanied by impressionistic orchestral music, in which he appeared as nine characters, only one of which vaguely resembled Bip, who visit or work in a city park. But after the Don Juan production, he stopped producing mimodramas, although when he opened his school in 1978, he called it the Ecole Internationale de Mimodrame de Paris Marcel Marceau. He said the reason he stopped producing mimodramas was because, despite his international success as a solo mime, he could not secure government subsidies for his company (Fifield 1968: 156). In 1955-1956, he toured Canada and the United States, performing his solo act featuring Bip. Audiences in cities across America responded euphorically, adoringly, and this incredible triumph propelled him to worldwide acclamation. From then on, he toured prodigiously throughout the world almost until he died. He performed everywhere on television and people everywhere who otherwise knew nothing about mime or pantomime knew of Marcel Marceau. Over the decades, his solo programs consisted of a series of “sketches,” each usually about three to five minutes long, in which Bip mimed his relationship to invisible objects against an empty background, as if he inhabited a space without any context. Bip changed only slightly from when Marceau invented him in 1946: in addition to the white face and Pierrotesque makeup, he wore white sailor pants, a white or dark half-jacket, a striped T-shirt, and often, though not always, a shabby opera hat with a large red carnation. The sketches presented Bip in a variety of activities: catching a butterfly, with his fluttering left hand simulating the insect, a lion tamer frustrated by the failure of his lion to leap through a hoop, a waiter serving a dish to a dissatisfied customer, Bip trying on different masks that distort his face, Bip dancing a comic tango, Bip playing a matador. Bip was not always in a comic mood and occasionally slipped into moments of pathos, as in a sketch in which he mimed the stages of life from birth, to childhood, to youth, to maturity, to old age, and to death; “The Cage” showed Bip attempting to break through invisible walls that surround him and finally sinking into apparently fatal resignation. Nearly all of the sketches dated from the 1950s, and even sketches produced after then remained faithful to what Bip was in the early 1950s. Bip’s immense popularity seemed to derive from his power to signify the unchanging, eternal solitude of “humanity” without speech, the charming and even absurd “innocence” of humanity when speech did not corrupt it. Yet Marceau was well aware that Bip entirely controlled his pantomimic imagination and prevented him from achieving much success outside of Bip, such as the mimodramas: “But I am a prisoner of my art. People do not want to see me as a character other than Bip” (Andriotakis 1979: Paragraph 7).

No one in the mime culture ever achieved the popularity of Marcel Marceau; it was as if the world needed no more popular or even equally popular mime artist than Marceau or needed any larger idea of mime or pantomime than that represented by Bip/Marceau. Bip projected a harmless, charming, friendly, congenially “segmented” image of solitary human innocence unencumbered by words or contaminated by any despoiling context. He was amusing, without being particularly funny, for to be funny, Bip would have to traffic in nasty caricatures, display some satiric bitterness, disclose people or situations worth ridiculing, reveal a disillusioned attitude toward life. The postwar theater and literary worlds assumed that audiences had no interest in seeing pantomime explore the sometimes demonic, sometimes grandiose, but always adventurous paths opened up earlier by the Austro-German pantomime culture, the silent film, or even the Cercle Funambulesque. Postwar ballet and modern dance could move into shadowy, disillusioning, or at least not “innocent” zones of human experience without losing their audiences, as seen, for example, in the work of Martha Graham, Jerome Robbins, Peter Darrell, or Dore Hoyer. It seems incredible that theater people everywhere could not imagine pantomime as anything more than the French idea of it as a very small scale, nostalgic, repetitive remodeling of Pierrot and Chaplin’s “Tramp” figure; otherwise, it was an activity left for schools to do as “preparation” for something more ambitious than pantomime itself. Marceau conveniently embodied the limits or summit of pantomime, which implicitly were the limits of the unregulated, speechless body in performance. The English novelist Mave Fellowes (b. 1980), the author of a novel, Chaplin & Company (2013), about a young woman who desires to become a mime like Marcel Marceau, has insightfully remarked that “after Marceau, there was nowhere left to go. I think he took his particular style—he was the best at it there could ever be. There was no room for further evolution, and no one has yet come up with another version of mime which is as appealing” (Hartnett 2014: Paragraphs 6-7).