Pantomime: The History and Metamorphosis of a Theatrical Ideology: Table of Contents

PDF version of the entire book.

Pantomime: a European Emblem of Modernity

Still, the war definitely had an impact on the cultural landscape of the West, including pantomime. The appetite for wordless performance outside of film was large. The 1920s was an exuberant, immensely innovative period in the history of dance. In Paris, throughout the decade, the famous Ballet Russes (1909-1929) continued its pre-war agenda of producing works that brought together leading modernists in choreography, music, and the visual arts. Under the direction of the impresario Sergei Diaghilev (1872-1929), the Ballet Russes freed ballet from the rigidity of state-subsidized ballet companies and their auxiliary academies. Diaghilev cultivated dance as an extravagant art that not only stirred bodies to spectacular expressions of glamor and dynamism but stimulated composers and visual artists to expand considerably the borders of their imaginations. The Ballet Russes established ballet as a modernist project that made the dancer the catalyst for an exhilarating intersection of the most advanced visual, musical, and choreographic arts. The Ballet Suedois (1920-1925), also in Paris and master-minded by Rolf de Maré (1888-1964), emulated Diaghilev’s strategy of redefining ballet by organizing the collaboration of extremely adventurous dancers with prominent modernist composers and visual artists. This company’s works, choreographed almost entirely by the blazingly and self-destructively brilliant Jean Börlin (1893-1930), were perhaps even more radical in their departure from classical ballet aesthetics than the Ballet Russes, reaching an apex with Relâche (1924), an almost Dadaistic experiment incorporating a nonsensical film (directed by René Clair), super-abstract sets by Francis Picabia, music by Erik Satie, and choreography that produced a complete “rupture, a break, with traditional ballet,” in which the almost total freedom from classical technique—that is, “as rapid and agreeable a movement as that procured by a 300 HP engine on the best road, lined with trees slanting in the illusion created by speed”—was synonymous with freedom from any conventional narrative coherence: instead, “a sensation of newness, of pleasure, the sensation of forgetting that one has to ‘think’ and ‘know’ something in order to like something” (Häger 1990: 252; cf., Claustrat 2012). But in his efforts to release ballet from classical technique, Börlin apparently flirted with pantomime. In 1920, he devised what he called “mimed scenes,” which sought to bring to life numerous figures from a painting of a storm approaching Toledo by the Spanish artist El Greco (1541-1614) and convincingly recreated by the head painter of the Paris Opera, Georges Mouveau (1878-1959). This expressionistic piece, with music composed by Désiré-Émile Inghelbrecht (1880-1965) after Börlin had designed the action/choreography, “contained nothing that was currently understood as dance.” “As with El Greco, the focus of activity lay in the arms, torso and head. There was less emphasis on the legs: the characters, more or less glued to the stage, danced on the spot,” and enacted a wide range of figures from El Greco, defined, so to speak, by the characterizing arm, head, and torso movements that fixed their “places” in the dark image of the city under the storm, including priests, aristocrats, a heretic, a victim of lightning, a girl converting the heretic, and devout pilgrims: “the dynamism of the baroque […] has been liberated and transformed into mimicry of life” (Häger 1990: 18-19, 104-109; De Groote 2002: 34-35). But despite the excitement aroused by El Greco, Börlin quickly moved away from expressionism and any intimation of pantomime: he wanted to embrace a more radiant Parisian-Mediterranean idea of freedom through release from Northern seriousness, with its stress on the dark emotional logic that animates bodies. But Börlin was not the only one in Paris thinking of pantomime as a form of anti-ballet. In 1920, the Swiss composer Arthur Honegger (1892-1955), who soon worked with Börlin, collaborated with the French illustrator and theatrical designer Guy Fauconnet (1882-1920) on what was originally to be a twenty-minute ballet, Horace victorieux, from a scenario by Fauconnet, who based his story on an anecdote in Livy. When Fauconnet died suddenly, the plan to stage the work collapsed; Honegger arranged the music, quite somber and heavy with expressionistic harmonies, as a “symphonic mime,” for indeed the music is far more suited to stark pantomimic action than to sleek balletic movements (Meylen 1982: 31-33). When the premiere of the music with the scenario took place in Essen, Germany in 1928, it was as a semi-pantomime, choreographed by Jens Keith (1898-1958), which preceded a performance of Honegger’s expressionistic opera Antigone (1927). The reception, however, was “frankly hostile,” presumably because the program was too intensely dissonant (Halbreich 1999: 114). But more information about the scenario and the performance is necessary to determine the significance of Horace victorieux, which, unfortunately, has not received any subsequent theatrical performance in spite of its extraordinary, though not “dancey,” music, for ballet companies continue to ignore it.

In their attempts to redefine ballet, the Ballet Russes and especially the Ballet Suedois revived ancient uncertainties about the distinction between ballet and pantomime (non-dance). Since the eighteenth century, ballet had striven to “free” itself from pantomime and to subordinate narrative to the greater goal of displaying graceful movement. Even when pantomime appeared in ballet, as it does in some of the older masterworks, it had to follow the “rules” of classical ballet technique for pantomime, as articulated by the revered ballet master Carlo Blasis (1797-1878), who explained, in his Code of Terpsichore (1820), that “Every action in pantomime must be regulated by the music” and that pantomime achieves sufficient emotional power only when performed by dancers proficient in ballet technique (Blasis 1830: 122, 127). Familiar with Lucian’s writings on ancient Roman pantomime, Blasis, regarded pantomime as a foundational platform in the evolution of ballet: “Pantomime is, undoubtedly, the very soul and support of the Ballet,” and if in ballet pantomime no longer seems a significant element, it is because composers (not choreographers!) “have not sufficient talent to put Pantomime upon an equality with dancing” (Blasis 1830: 121). But within ballet culture, Blasis’ evolutionary idea of pantomime as a primal or fundamental phase of ballet history meant that ballet could only evolve to the ever-higher phase of its history by diminishing or altogether eliminating pantomime as a goal of performance. At any rate, Blasis inadvertently made pantomime seem like a disorderly or neglected form of dance in need of strict regulation. In reality, however, the regulation of pantomime meant the subordination of narrative to the display of movement. By the end of the nineteenth century, the distinction between ballet and pantomime was clear, which we may summarize as follows. While gestures generally operate within a code or system of signs, a common misunderstanding about pantomime is that it “translates” words into gestures or physical movements. But pantomime is best when it follows its own system of signification rather than translates from one system to another. More precisely, pantomime emphasizes action over movement. Actions, of course, contain movements. But in pantomime, the performer thinks in terms of completing an action and then initiating another one, so that one action follows another. Pantomime shows how the body narrates. The performance of these actions does not follow any “rules” of movement; rather, the performer finds the best, most efficient way to perform the action, usually in a manner unique to the performer. What is important is the relation of one action to the next, how well the performer connects one action to another according to a “feeling” that is signified while performing the actions. In dance, especially ballet, what is important is movement itself, the formal beauty of the body in motion. In pantomime, a performer will pick up a glass of wine, take a sip, then study messages on an iPhone, while also signifying that he is maybe in an exuberant mood … or sad or filled with anxiety or cheerful and then suddenly surprised by a message. This is a set of actions. In dance, the tendency is to use the narrative as a basis for displaying the beauty of a body in motion, an excuse for showing off movements. The dancer picks up a glass of wine off a table, holds it high, then pirouettes with the glass, rises on pointe with the glass, then rushes in a great arc over the stage. The idea is: “Look, I have a glass of wine! See what I can do holding this glass of wine. Behold the beautiful movements I can make holding this glass of wine. Look how my body shows the exhilarating thrill of taking the first sip!” The idea in pantomime is to show how the body alone constructs a narrative by moving from one action to another according to a logic signified physically. It is about the power of the body to narrate. The idea in ballet is that the body disrupts narrative control over it–to a great degree it is about how the body frees itself from narrative and follows its own “rules.” Dance is about movements of the body that are interesting in themselves, and what makes them interesting is often what they reveal about the dancers or dance itself rather than about anything outside of dance. But dance (especially ballet!) is always about “rules,” the regulation of the body by a system external to it, about steps, positions, a vocabulary of movements that determine the beauty or value of the art. These rules do not come from the performers; they come from movement systems, from schools. Dancers are always evaluated in relation to their adherence to the “system” or school to which they belong. Pantomimes are generally evaluated in relation to the characters they represent, their ability to represent identities outside of their own and outside of any system controlling their bodies.

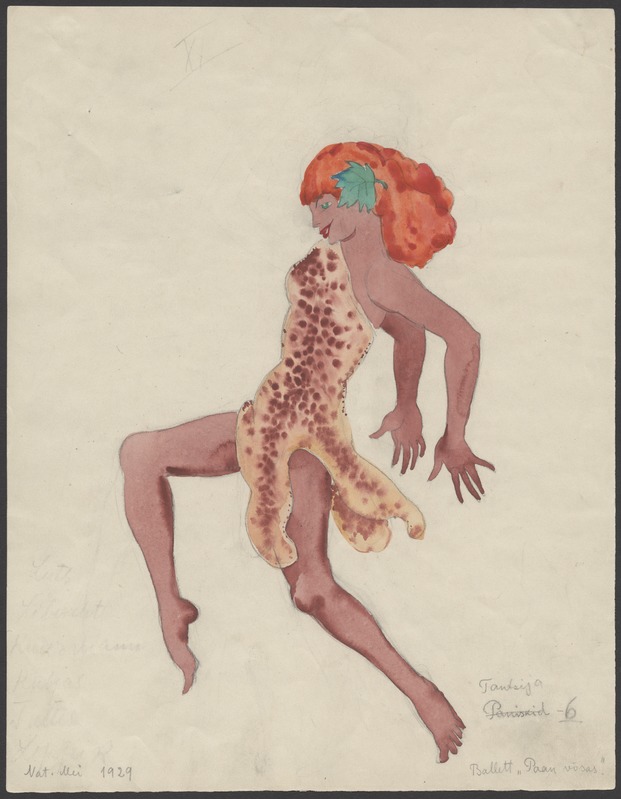

But by 1920, as a result of the Ballet Russes and the Ballet Suedois, the distinction between ballet and pantomime became muddled, even though neither company had a deep interest in pantomime, simply because the companies sought to change the rules of ballet by incorporating modernist visual and sonic dimensions that somehow “compromised” the glorification of movement in itself. In Germany, which had no strong ballet tradition of its own, probably abetted by Wagner’s notorious aversion to dance in opera, the distinction was perhaps even more muddled. In the days before the terms “Ausdruckstanz” and “Freie Tanz” designated modern dance, Germans used a variety of terms to describe the non-balletic artistic theatrical dance for which the country was a major producer: “Tanzpantomime,” “Tanzspiel,” “Tanzdrama,” “Tanzdichtung.” For awhile, Rudolf Laban used the term “Choreodrama,” apparently without knowing that the term had been applied to Viganò’s productions over a hundred years earlier. In 1925, Emil Reznicek (1860-1945) composed a large-scale “Tanz-Sinfonie: Marionetten des Todes,” which had a production at the Dresden Opera in 1927, with choreography and apparently scenario by that connoisseur of luxuriously bizarre dance performance Ellen Petz (1899-1970), who had shifted from ballet to modern dance during the war (cf. Toepfer 1997: 286). The tendency nowadays is to refer to the symphony as “ballet music,” but Reznicek classified the movements of the symphony according to folk dance forms: Polonaise, Csárdás, Ländler, Tarantella, and Petz used the movements to create four “images” of an opulent, aristocratic milieu from the seventeenth century without calling it a ballet, although information about this production, as with all of Petz’s mysterious work, remains maddeningly obscure. Possibly the first to coin a German term for non-balletic art dancing was Otto Julius Bierbaum (1865-1910), with his scenario for Pan im Busch (1899), which he called a “Tanzspiel” or “dance play,” a term used previously, extremely rarely, in an anthropological context to refer to festive dance rituals in folk or non-Western societies. This piece contrasted the amorous adventures of some school children haplessly supervised by a Professor and Governess in a twilight grove with the amorous gamboling of fauns and “panisci” (female fauns) encouraged by the lascivious, flute-playing Pan and his consort Aphrodite. As night falls, the difference between dream and reality dissolves, and a romantic pair who have fallen asleep in the grove become a shepherd and nymph, worshippers of Pan and Aphrodite. But after a storm, the school children return with lanterns: the Professor and Governess forgive the stray students and the piece concludes with a rousing ensemble dance in gallop tempo, with Pan’s head appearing “between the lanterns” (Bierbaum 1900). Pan im Busch combines pantomime with processional movements, poses, and different kinds of dances (round dances, waltzes, polonaise); with its numerous decorative effects, such as the procession of lanterns, an inundation of rose petals, and Aphrodite in white chiton, gold sandals, and gold ornaments, the piece resembles an erotic festival pageant or a hothouse erotic ceremony. It is certainly not a ballet. Bierbaum sought to engage Richard Strauss to write the music, for Strauss was always looking for opportunities to compose for the theater. But he didn’t see one in Bierbaum’s scenario (Heisler 2009: 38-39). So Bierbaum’s friend, the Wagnerian conductor Felix Mottl (1856-1911), wrote the orchestral score, and the work had a production at the Karlsruhe Opera in March 1900 that employed such a densely lush forest setting that it is difficult to see how any kind of dancing could take place on the stage (Bühne und Welt v.2 pt.2 1900: 624; Draheim 2004: 109). But this odd work managed to have another production thirty years later, in Tallinn, Estonia. At the Estonia Theater, Rahel Olbrei (1898-1984), the opera ballet director, staged the piece in December 1929 using both actors and dancers and an expressionist set designed by Aleksander Tuurand (1888-1936) that provided space for dancing, although critics complained that the dances went on too long and with too much “bustle.” Olbrei took a more blatantly erotic approach to the scenario than the Karlsruhe production by stressing voluptuous movements, lifts, and poses. But the acting succeeded more than the dancing, which combined ballet with German modern dance. The ballet company was only three years old, and Olbrei was struggling to build a reliable, distinctive unit with the limited talent and resources available to her. A “Tanzspiel” seemed a way to disguise these limitations, but the critic Henrik Visnapuu (1890-1951) warned that “dance pantomime,” as he called it, required as much talent as ballet and was by implication not a term to which one should attach lowered artistic expectations (Leis 2006: 31; Einasto 2018: 129-131).

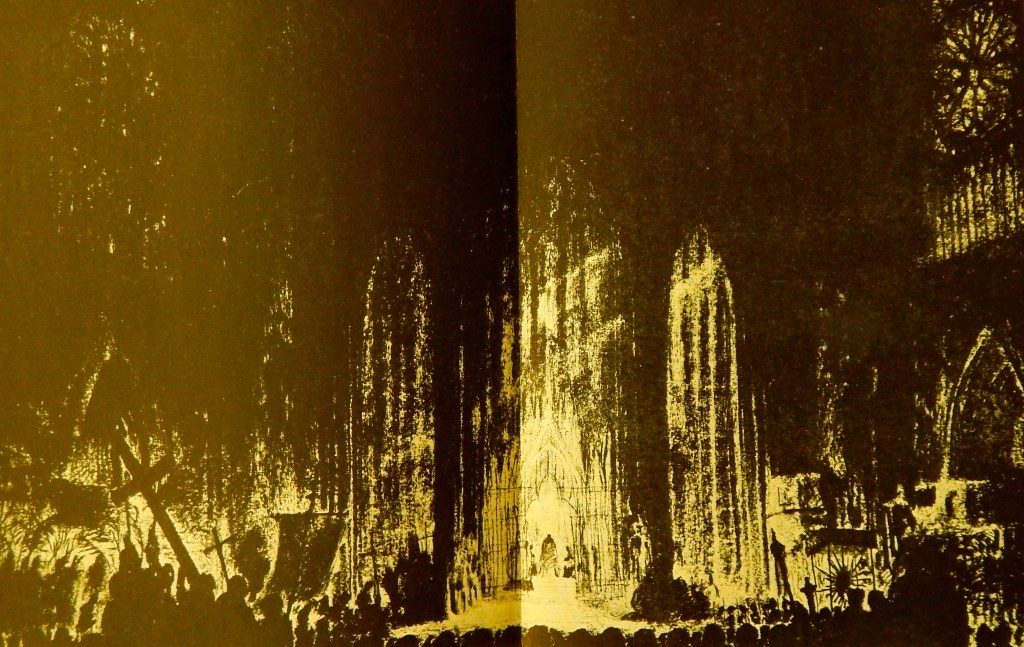

As explained earlier, the modern solo dance concert program resembled the ancient Roman pantomime in its exploration of the metamorphosis of the performer’s body through the combination of pantomimic and dance movements. By 1924, however, the solo modern dance concert was in steep decline: modern dance, with its new schools, favored ensemble pieces that emphasized formal complexity, abstraction, and the power of movement to free bodies from the constraints on identity imposed upon them by too easily decipherable narratives. But pantomime was by no means dead, and perhaps enjoyed a wider range of actual performances than during the period 1900 to 1913, even if fewer people could claim “authorship” of it. The revival of Reinhardt’s Das Mirakel in 1924-1925 achieved great popular success, but for the most part during the 1920s pantomime in the theater appealed to modernist, even avant-garde sensibilities. But of course, sometimes the pantomimic imagination was difficult to manage, even for quite experimental artists in an era famous for experimentation in the arts. For example, in 1920, the Russian composer Sonia Fridman, later known as Sophie-Carmen Eckhardt-Gramatté (1899-1974), met and married the expressionist artist Walter Gramatté (1897-1929) in Berlin. Since 1914, when she had lived in Paris, Fridman had worked on the scenario and music for a pantomime called Ziganka. Her marriage to Gramatté caused her to move the pantomime project into alignment with the dark, eerie mysticism of his paintings. The scenario takes place in a mountainous landscape of the unconscious of a dreaming man—or boy, since the “symphonic pantomime” now bore the title Der träumende Knabe. In its brief three acts, the scenario describes the desire of a Man to unite with an idealized female figure, Ziganka, whom he encounters in a nocturnal mountain pass. Ziganka is actually “the personified thought of the Man,” a feminized version of himself. A tribe of demons, residing in caves filled with red light, tries to persuade the Man to join them and abjure Ziganka. But the Man remains fixated on Ziganka; he performs various gestures to invite her to come close to him, and they perform a dance duet that ends in a kiss. Yet Ziganka remains sad and reteats from him into a deepening darkness. The Man falls asleep in the red cave of the demons, who perform ecstatic actions that emulate the movements of Ziganka. A “red” Ziganka (performed by the same actor who plays the “ideal” Ziganka) appears and dances with the Man, and this dance also ends in a “deep kiss.” The Man realizes the demons have tricked him and he turns against them: the stage fills with screams and red light. As a storm invades the scene, the real Ziganka enters with an entourage of “The Good Ones” and instructs them to dispel the demons, while she herself disappears into the foggy blue horizon. After The Good Ones defeat The Evil Ones, the Man appears and implores The Good Ones to bring him to Ziganka, but The Good Ones block the way. In the final act, the Man wanders alone along a path, at the end of which he encounters the lifeless figure or statue of Ziganka. He is in a forest of “blue trees and black sky.” The stage fills with ecstatic female figures and the sky turns purple. Different female figures attempt to dance with the Man, but he rejects them, while they each mock him and disappear. A scrim falls before the Man to signify that “a world emerges from which the Man remains excluded until the end.” In the background, a mountain rises with a steep stairway. Ziganka and her entourage appear; she shakes her head sadly and gestures to signify: “I live only in your heart, in your imagination; I cannot stay.” After she bows affectionately to him, she and her entourage turn away and ascend the stairs. As the stage becomes darker, Ziganka becomes brighter and brighter. Then, quickly the light fades on her to reveal the upraised arms of the Man, until these, too, go dark with the “dying of the music” (Schulz-Hoffmann 1987: 37-45). The piece makes use of numerous light and color effects, especially a shifting contrast between blue and red. Powerful light shines from stars, from caves, from clouds, from Ziganka. Particularly imaginative is the appearance of three little demons with mirrors attached to their backs. Dancing takes place in all three acts, but most of the action consists of symbolic gestures: imploring, kneeling, summoning, turning away, pointing, trembling, convulsing, reaching, being thrown back, kissing, among others, conveying somewhat the image of bodies moving in a trance. But the piece also includes moments when Ziganka assumes a pose of stillness. As preparation for the production of the pantomime in Berlin, Walter Gramatté drew twenty-two expressionistic pastel images of actions in the piece as a way to visualize the action on stage [Figure 136] (Schulz-Hoffmann 1987). He hoped to direct the production, and in a letter to Sonia, in which he compares her to a hovering angel, he claims that even if he doesn’t direct the piece, their work together will hover similarly above their graves, to be discovered by future generations lamenting the “alien” treatment of the couple’s work by the present society (13-14). But even before she had met Gramatté, Sonia had a sponsor, the economist, venture capitalist, and occasional literary author Robert Friedlaender-Prachtl (1874-1950), who cultivated a multi-faceted passion for theater throughout his life. Sonia envisioned a large-scale symphonic musical accompaniment, but she had limited skill at orchestration. In 1918, Friedlaender-Prachtl contracted with the conductor Hermann Scherchen (1891-1966) to orchestrate Fridman’s music, which Scherchen apparently completed before Fridman met Gramatté. However, Sonia’s life with Walter caused her to make revisions in the scenario. Walter planned to stage the production at the Berlin Staatstheater in 1921 with possibly the solo dancers Niddy Impekoven or Sent M’ahesa playing Ziganka. But the performance never took place, despite the encouragement of such illustrious Berlin theater figures as Ludwig Berger and Paul Wegener, although a performance of the prelude, orchestrated by Sonia’s friend Adam Szpak (1887-1953), occurred at a philharmonic concert in Hamburg in 1923. Her second husband, the art historian Ferdinand Eckhardt (1902-1995), claims that the reason Das träumende Knabe never received a performance was because Sonia kept changing her mind about the piece and never reached a point of deciding it was complete (11-12, 35-36). It may seem, from the scenario and Gramatté’s pictures, that the “symphonic pantomime” dramatizes the failure of the male to unite with the idealized female of his imagination to produce the “work” that allows him to transcend the impure material world. But perhaps for Sonia the piece could never be finished because she kept adding male collaborators, and she could not be sure how to complete herself through any of them. The piece might well be a fascinating critique of male desire, but presumably for Sonia it was not sufficiently autobiographical, not sufficiently “her own.”

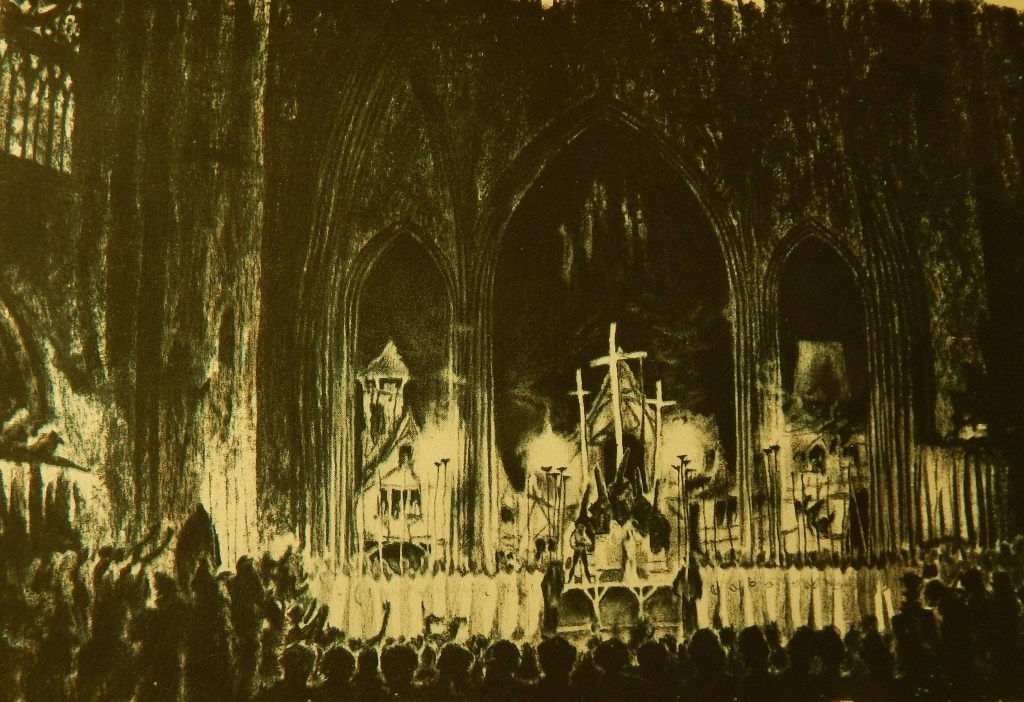

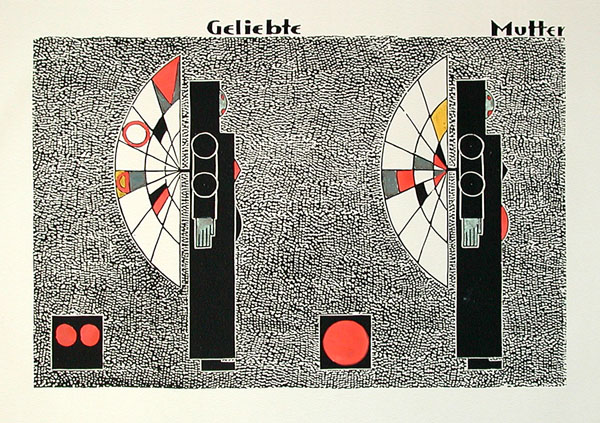

Even so, Sonia Fridman saw expressionist pantomime as a mystical-psychoanalytic convergence of colors, sounds, and movements wherein the body followed a psychic “path” or light that was quite different from the intellectually turbulent, socio-critical expressionism in the pantomime projects of Carl Einstein, Ludwig Rubiner, and Walter Hasenclever. An even more radical expressionist mysticism pervaded the pantomime thinking of the German artist and theater producer Lothar Schreyer (1886-1966). After studying law, Schreyer turned his attention to the theater in Berlin, where he worked as an assistant director in the Deutsches Schauspielhaus. In 1914, he began working with Herwarth Walden (1879-1941), the editor of Der Sturm, the most famous of the expressionist periodicals. In 1916, Walden began publishing in the journal Schreyer’s short, expressionist plays, which consisted largely of dialogue uttered in one, two or three-word phrases, as if the archetypal characters speak primarily to hear the music of the words. By 1918, Walden and Schreyer had founded the Sturm-Bühne, a theater devoted to the production of experimental expressionist plays by Schreyer, Walden, and August Stramm, which all featured somber expressionistic poetic dialogue in the “telegraphic” style spoken by archetypal figures in vague, abstract spaces. Schreyer was supposedly also an instructor at the Sturm-Bühne Schule für Bühnenkunst und Pantomime, but its difficult to determine what this school actually did other than recruit people to work on projects for the Sturm-Bühne. From 1916 on, Schreyer published numerous polemical and promotional essays in which he proposed that expressionism must abandon drama and any conventional idea of theater and instead focus on the creation of “stage artworks” (“Bühnenkunstwerk”). He saw the stage artwork as fundamental to the building of a new society, a new human identity, released from materialsim and transfigured, ecstatically, by a new, modern mode of spirituality. The stage artwork resulted from a highly precise coordination of sound, color, and movement, so that all of these elements unfolded in relation to each other on the stage like notes in a musical score. Indeed, with Kreuzigung (1920), Schreyer composed what he called a “Spielgang,” which was an elaborate pictorial notational system that assigned a cryptic tonality and rhythm to the performance of every word, gesture, sound, image, and color. The “characters” in these stage artworks were allegorical, super-archetypal figures (“Mother,” “Beloved,” “Death,” “Child”), supposedly completely without individuality, which Schreyer regarded as a corrupting phenomenon within modern society. Yet he designed elaborate, highly unique, intensely geometric mask-costumes for these characters so that they looked like fantastically engineered super-dolls or robots. The idea of the stage artwork was not to see a play, but to experience the movement of a very modern image-sculpture in relation to various, intricate permutations of sound, color, and utterance [Figure 137].

Like the Ballet Russes and the Ballet Suedois, Schreyer believed that modernist visual effects changed the way people saw human movement; the path to a new, ecstatic society entailed new rhythmic relations between voice, gesture, color, light, and sound, all of which, in their lunge toward abstraction, turned the performing body itself into something resembling an alien idol. In recollecting his years with the Sturm-Bühne, Schreyer claimed (1948) Scheerbart’s pantomime Kometentanz (1903) had inspired him as had the 1920 Dresden production of William Wauer’s pantomime Die vier Toten der Fiametta (Schreyer 2001: 298, 307). “In every pantomime lies a full and complete action in itself that […] creates a connection between objective and subjective life, in which the objective life bears the subjective and the subjective life discloses the objective. Pantomime is theater. We sought to form it as an expressionistic play of movement” (Schreyer 2001: 297). Yet Schreyer was unable to create any stage artworks without his allegorical robot-characters uttering words, cries, ecstatic telegraphic phrases. He needed a lyricism in performance that he simply could not imagine for the body, which he saw as something requiring completely new engineering, a new geometrical-mathematical relation to color, space, sound, and language. These ideas caused him difficulties. His mysticism provoked tension with Walden, who became fervently attached to socialism. In 1919, Schreyer moved briefly to Hamburg, where he founded the Kampf-Bühne, which, as discussed below, came closer to a mystical expressionist idea of pantomime under the leadership of his protégé Lavinia Schulz (cf. Schreyer 1985: 147-148). His brilliant visual imagination caught the attention of the architect Walter Gropius (1883-1969), who invited him (1921) to teach in the theater section of the newly formed Bauhaus arts academy in Weimar. But when Schreyer staged his two-character (“Man/Moon,” “Woman/Earth/Mother”) Mondspiel at the school in 1923, the students complained about the cultish obscurity of the work, and Gropius himself believed that Schreyer’s expressionism was no longer helpful in designing the products, structures, and forms of modern society. Schreyer resigned. He continued to publish many programmatic articles on theater and performance while pursuing various academic, literary, and religious projects, but he never returned to any creative work in the theater. Yet he understood more clearly than anyone in Paris or in the Bauhaus how a radical image of modernity, including an even more radical image of the body (as an engineered idol), caused even the simplest movements of the body to provoke deeply disconcerting, even violent emotions that obscured the distinction between subjectivity and objectivity, a confusion that, from the expressionist perspective, was necessary to change the subject’s relation to reality and thus move people toward the creation of a new, redemptive society. Schreyer’s ideas probably influenced Oskar Schlemmer (1888-1943) in the development of his Triadic Ballet, the most famous theatrical work of the Bauhaus. Schlemmer began work on this thirty-minute piece in 1915 and he never really finished it when the Bauhaus stopped performing it in 1929. The piece encountered manifold problems related to music, narrative structure, design, and production (cf. Scheper 1988). But perhaps the biggest problem was that Schlemmer invested too much energy into the design of the modernist costumes, many of which were bulbous, heavily geometric, and somewhat clownish. All movement, action, and narrative for the three dancers had to be built around the capability of the costumes to permit anything gestural. The result is like watching a bizarre fashion show: the movement exists to display the costumes. The dancers look like a set of large, animated toys performing mechanically in yellow, pink, and finally dark chessboard spaces. But this image of modernity was obviously much more comforting or soothing than Schreyer’s dark idols or totems for a new religion of modernity.

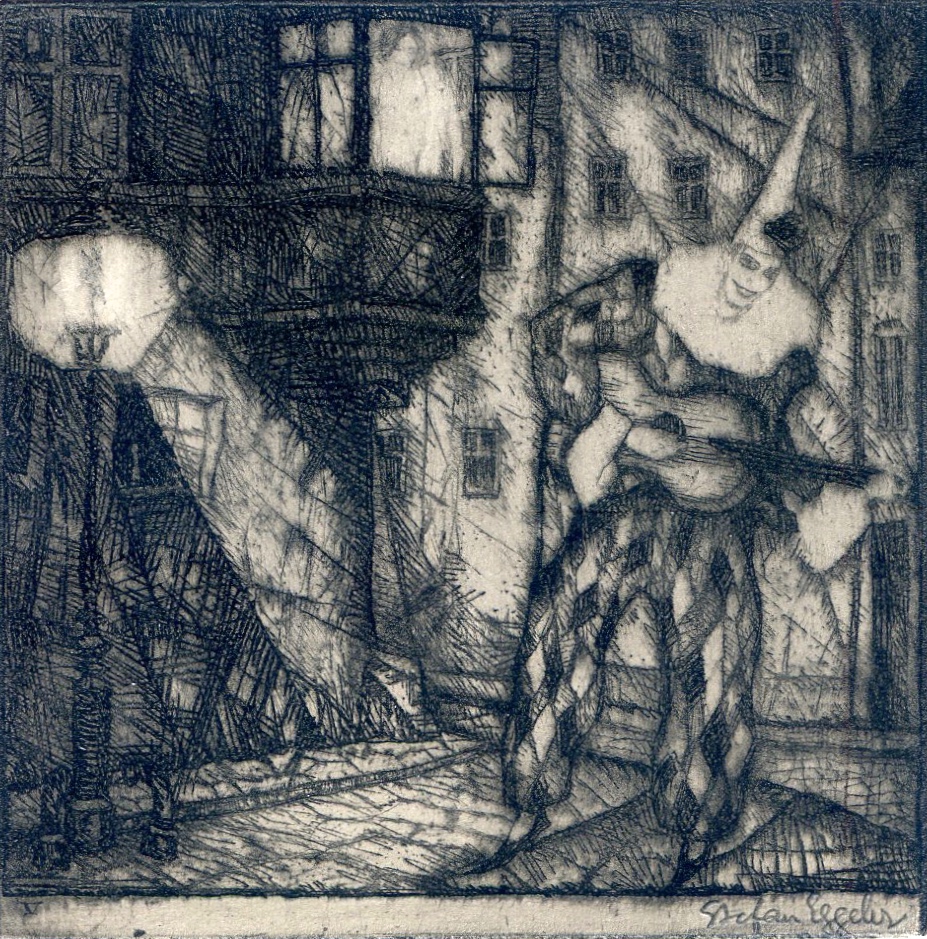

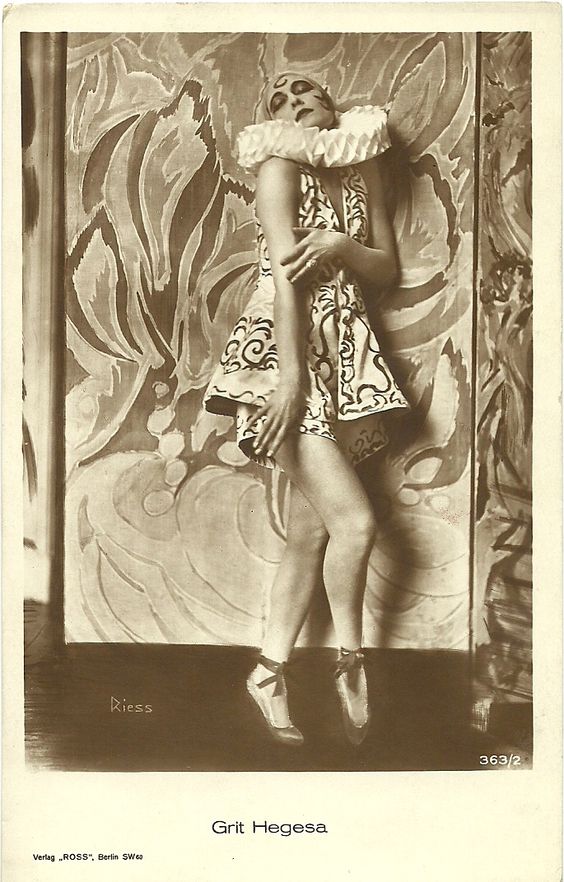

In his ambition to make theater a kind of high tech shrine for the convergence of mysticism and modernism, Schreyer cited the 1920 production of William Wauer’s pantomime Die vier Toten der Fiametta as an inspiration for the new theater aesthetic. Yet this pantomime arose from a much different modernist ambition. The piece had its first production at the Kleines Theater, Berlin, in June 1911 as the first theatrical event sponsored by Der Sturm. Herwarth Walden composed and performed the piano accompaniment. The artist historian turned theater director William Wauer (1866-1962) directed the production, but evidently he did not write or need a scenario, for none was ever published, although an advertisement for the production acknowledged that he adapted a one-act play by an obscure writer of operetta libretti, Alexander Pordes-Milo (1878-1931). In a 1909 book on “art in the theater,” Wauer asserted that, “The director is neither the lawyer nor the servant of the poet. He faces the poetry, like the painter nature, the landscape. He uses it as a motive, as a pretext, to produce his art” (Wauer 1909: 13). Wauer soon became a director of silent films, including Richard Wagner (1913), the science fiction drama Der Tunnel(1915), and many others until 1921. The poet Elisabeth Lasker-Schüler (1869-1945), who was at that time married to Walden, became enamored with Wauer’s “anatomical” directing and was eager to have him direct her 1908 drama Die Wupper. She attended a 1910 café lecture by Wauer in which he conducted his audience, mostly students, as if they were instruments of an orchestra, which is how Wauer himself described the role of the theater director in relation to actors (Lasker-Schüler 1914: 115-116; Wauer 1909: 12). Because, however, Die vier Toten der Fiametta lacked a written scenario, it is necessary to rely on the written description of the performance by the novelist Alfred Döblin (1878-1957) in a lengthy review of the piece in Der Sturm (No. 67, 11 July 1911: 531-533). According to Döblin’s scanty description of the story, the pantomime concerns the marriage between a hunchback tailor, Silvio, played by Wauer himself, and his wife, Fiametta, played by the cabaret artist and soon very busy film actress Rosa Valetti (1878-1937). Fiametta feels stifled in her marriage and takes on lovers in succession, three altogether, whom Döblin describes as “harlequins,” each played by a different actor. The jealous Silvio arranges to have each lover killed “accidentally,” thrown out of a window by a drunken beggar, believing that all the lovers are actually one and the same man come back to life. But Fiametta experiences each death as a liberation. In a drunken fury, Silvio, believing himself to be her fourth lover, winds up hurling himself to death. “Fiametta remains triumphant, the symbol of invincibility, the marriage-mocker, alone, if also never abandoned.” It was apparently a dark production. Döblin calls it a “tragedy,” Lasker-Schüler a “Trauerspiel” (sad play); reviewers called it violent, bloody, but not comical, even though on the program it appeared between a performance of Offenbach’s one-act operetta Der verwandelte Katze (1858) and something called Karneval in Nizza with music by Hans Roland (aka Wilhelm Guttmann [1886-1941]). The production elicited numerous reviews, nearly all of which were negative and most of which complained of Walden’s terrible, noisy, “raw,” “childish,” “naïve,” and completely inappropriate music. One critic remarked that the music had completely destroyed his nervous system. Walden devoted two entire huge pages of Der Sturm, with a third page written by the literary critic Josef Adler, to defend his music and quote all the accusations against it (No. 66, 24 June 1911: 523-525). Walden and Adler questioned the competence of the reviewers to assess the music, for the reviewers had praised the trivial music of Offenbach and Roland without seeming to realize that Walden’s music functioned in opposition to the aims of Offenbach and Roland, as if Die vier Toten der Fiametta existed as a drastic contrast rather than complement to the other pieces. The implication is that Walden’s music was a critique or parody of the bourgeois entertainments associated with Offenbach and Roland, but the implication lacks verification, because Walden never published the music, although he published many other compositions. Döblin was more direct in his favorable evaluation of the production as a whole. He treated the pantomime as a critique of marriage insofar as marriage is a “cage,” for “Marriage is perhaps the most sinister production of the human spirit, eerie not for what it is as what it can be.” Fiametta “breaks out of her cage,” although it is not clear if the cage is Döblin’s metaphor or a scenic device-metaphor of the performance. He does, however, refer to the pantomimic action: “it is not necessary that anyone speaks in this piece. The whole expressive dimension of the action can be exhausted in movement; nothing needs to be spoken. This linear expression is artistically best, because it is the narrowest and most concentrated,” an “economic” principle that allows “minimum force to be applied for maximum effect.” In this piece, the “movement of the mute pantomime” showed how a “leaden, rigid scheme” (the narrative? like a cage?) imposes itself on “the flow and abundance of the living process” and “imprints a naked dynamic and energy.” But then, Döblin turns his attention to defending the music of “my friend Herwarth Walden,” which he claims has been misunderstood by those who have criticized it. The music follows the same kind of “economy” as the pantomimic action by not following “the melodic or harmonic leadership of music from the past,” by avoiding ornamentation, and producing a “sculptural impression of a psychic unmasking,” an “essential […] actual dramatic music.” However, Döblin asserts that the pantomimic action follows the music, for it is the task of the director to “form optically what is sculpturally heard.” The music would be even stronger with an orchestra rather than with a solo piano.

Walden attached another set of negative press commentary to Döblin’s review, before inserting his own column praising Wauer’s direction and acting, which in its economy was like a poem by Lasker-Schüler, as well as the work of other actors. “William Wauer is without doubt the strongest directorial talent of our time,” for Wauer achieves a “sculptural expressiveness […] a monumentality of personality,” whereas Max Reinhardt, in his pantomime production of Sumurun, which had premiered the previous year, trafficked in “salon art” superficialities. With Wauer, “the art of pantomime becomes alive again, after the debris of tradition has been cleared away, and the strong breath of a personality has awakened it” (532-533). All of this commentary in Der Sturm stirred up considerable public curiosity about the production, which reached 25 performances, making it one of the most successful theater productions in all of Germany that year. Yet despite this success, neither Wauer nor Walden ventured further with pantomime in the theater. Wauer started directing films and Walden continued writing his “comitragedies” of unhappy marriages and dysfunctional families, all written entirely as spoken dialogue. But they did revive Die vier Toten der Fiametta in 1920, at the Albert Theater in Dresden on a double bill with a performance of Walden’s one-act, exclusively stichomythic dialogue “bourgeois comitragedy” Trieb (1918). Wauer again played Silvio, alternating with Hans Fritz Köllner (1896-1976), while two women, Maria Neukirchen and Evy Peter, took turns in the role of Fiametta, and four new men performed the three harlequins and the beggar. Walden conducted an orchestral accompaniment. Brian Keith-Smith has published a photo of a scene from the production (Schreyer 2001: 229). The image shows an expressionist interior with windows painted onto the cyclorama and even onto the ceiling like arabesque prison bars; the three lovers and Silvio appear in identical white pajama-like costumes and thus resemble Pierrots more than harlequins. Fiametta wears a tight blouse with a fur collar and a short, three-layered skirt. The production photo does evoke a Caligarian scenic atmosphere that seems unimaginable for the 1911 production, about which no one seems to have commented on the scenic design. The show enjoyed some success, because it ran from October 1920 until January 1921. In the Dresden press, Walden’s music was again a source of bitter complaint. His friend, the film actor and arts commentator Rudolf Blümner (1873-1945), wrote a long letter to Walden defending the music, which Walden published in Der Sturm (Vol. 11, September-October 1920: 132-135). According to Blümner, the critics now objected that the music was not sufficiently modern or expressionistic, that it contributed to turning the piece into a “banal ballet.” He scolded the critics for failing to grasp the difference between ballet and pantomime. Wauer and Walden, he announced, were “the first in Europe” to have “solved the problem” of the relation between music and pantomime, for they have recognized that music and “note-true gesture” do not operate in parallel (synchrony). Unfortunately, he did not elaborate on this point, which seems to suggest that the music comments on the action instead of prescribes it; at any rate, the music did not need to be expressionist to create an expressionist effect in the theater. Blümner then went on to explain that Walden’s “banal” music is similar to that of Beethoven in that it is “timeless” and non-nationalistic, for “your melodies and harmonies are not from yourself, but from the depths of human souls,” and thus the “cosmic banality” of Walden’s music transcended the decline of music that began with Wagner, continued with Debussy and Schönberg, and culminated in the decadent expressionism of Richard Strauss. Of course, it is difficult to take this defense seriously, which was perhaps the point, completely lost by the critics, who merely grumbled that Walden’s music had ruined an otherwise engaging pantomime performance. From Walden’s perspective, the pantomime was not mainly a critique of marriage, though this was an inescapable feature of the progam as a whole. It was a critique of critical values themselves, an attempt to transform negative values into positive—that was the point of publishing so many denunciations of the production, particularly of Walden’s music, next to patient, almost pedantic, explanations of why what was supposedly bad about the production was actually good, so that ultimately it was unclear if the pantomime was good or bad or if it was even relevant to appreciating the significance of the performance. Good or bad according to whom? According to what system of values designed by whom? Schreyer’s theatrical experiments showed how expressionist visual design radically changed perception of the simplest physical actions. Die vier Toten der Fiametta showed how even the most “banal” music radically changed perception of physical action and in doing so dramatized more effectively the murderous absurdity of marriage, a point perhaps obscured by the expressionist stage design. But Dresden was not the final stop for Die vier Toten der Fiametta. Walden’s enthusiasm for the Soviet revolution brought him into contact with the Moscow theater world. In 1928, Vselevod Meyerhold staged or at least planned a production of the pantomime in Moscow, although almost nothing is known about this production outside of Russia (Schreyer 2001: 231). Meyerhold had staged an earlier pantomime production with the same title in St. Petersburg in 1911, but claimed a different source material, “N.N.” (Nikolai Evreinov?), although the characters are the same and the plot almost identical to the Wauer-Walden scenario, except that Meyerhold’s production seems to contain some dialogue, and, to hide her lovers from Silvio, Fiametta stuffs them into a trunk, where they suffocate to death. Fiametta then uses gold coins to bribe a drunken beggar to throw the corpses out the window. He mistakes Silvio for another corpse and accidentally throws him out the window, to Fiametta’s immense pleasure. The relation between the Berlin and the St. Petersburg productions is obscure and tantalizing; of course, it would help to know when in 1911 Meyerhold staged his production. Perhaps both derive from an old commedia scenario. The St. Petersburg production was another of Meyerhold’s “cubist-metatheater” experiments with commedia dell’arte figures during his “Doctor Dapertutto” phase, although Meyerhold tended to treat pantomime and his eventually “biomechanical” idea of it as a component within a play rather than as a separate catgeory of performance (Clayton 1994: 250-253). So the 1928 Moscow project may have incorporated ideas from the 1911 productions in St. Petersburg and Berlin, as well as the 1920 Dresden production. It may be, though, that the evidence simply does not exist to decipher adequately the mysterious relationship between these German and Russian pantomime productions of the same story. But with the Walden-Wauer production of Die vier Toten der Fiametta, the goal was to undermine socially or institutionally constructed distinctions between expressionism and “banality,” between good and bad judgments of performance, between authors within collaboration, between gestural rhythm/tonality and musical rhythm/tonality, between actor and director, between one lover and another, between marriage and prison, between desire and destructiveness, between crime and “accident,” and between pantomimic wordlessness and extravagant critical verbosity.

Meanwhile, Schreyer’s expressionistic theater aesthetic found a foothold outside of Berlin. At the Kampf-Bühne, which he established in 1919 in Hamburg, a city seething with expressionistic activity, where he had accepted a position as dramaturge for the Deutsches Schauspielhaus, Schreyer produced in a separate small, private theater a couple of expressionist plays by August Stramm (1874-1915) and then embarked on productions of his own “stage artworks,” Krippenspiel, Skirnismol, Empedokles, Kreuzigung. The actress-artist Lavinia Schulz (1896-1924) had followed him to Hamburg, after working with him on a controversial 1918 production of Stramm’s Sancta Susanna (1913) at the Sturm-Bühne in Berlin. But as usual with Schreyer, he ran into conflict with his collaborators. His theory of the stage artwork assigned importance to sound but not to music in constructing the “Spielgang” for production. Or rather, he understood sound or music as coming entirely from the isolated words spoken by the allegorical stage characters, so that actors treated words and syllables of words as musical tropes, “scored,” in the “Spielgang,” in relation to colors, design elements, and movements. Schulz, however, felt that Schreyer’s obsession with full-body mask-costumes inhibited movement and suppressed imaginative use of music. She wanted a performance that eliminated words altogether. Schreyer contended that his work with Schulz came to an end because of her turbulent and sometimes violent relationship with her partner and eventual husband, Walter Holdt (1899-1924), who acted as well as built costumes for the Kampf-Bühne productions (Schreyer 2001: 599).

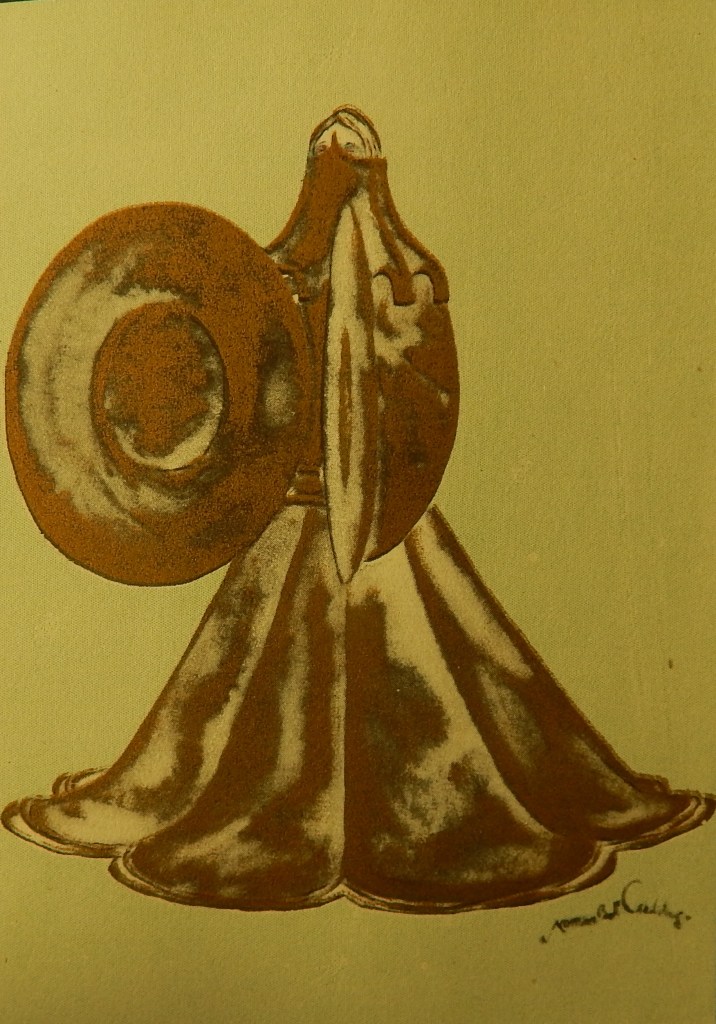

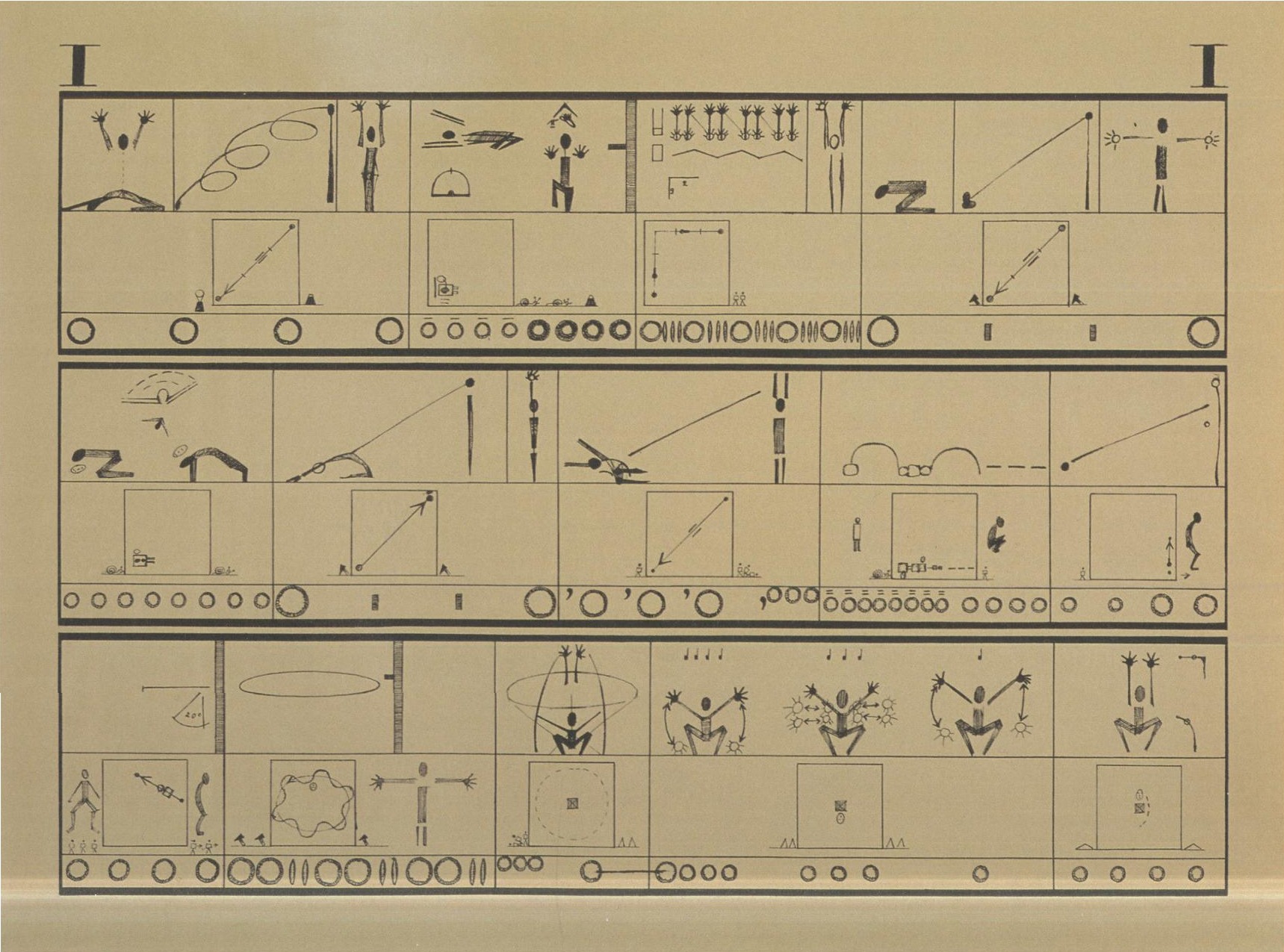

But Schulz’s artistic ambitions urged her to choose Holdt over Schreyer in shaping her performance aesthetic. Schreyer left for the Bauhaus, while Schulz and Holdt continued on their own in Hamburg. For Schulz, expressionism was no longer a power to construct an allegorical abstraction of human identity or a mystical “inner” condition; it was the power to transform human identity into an utterly alien form, a bizarre mutation, a grotesque species, sometimes insectoid, sometimes robotic, sometimes as if the performer’s body came from another world altogether. The wild costumes that she designed and Holdt built out of discarded materials certainly formed the strange identities of the creatures they created for the stage (Nuñez 2006: 56-63) [Figure 138]. But unlike Schreyer with his idol-like figures, Schulz was not content to let the expressionist costume design reveal the strangeness of the simplest human movements: she wanted a unique, ideologically informed movement to emerge from the costumes. She and Holdt befriended the young composer and musicologist Hans Heinz Stuckenschmidt (1901-1988), who played in a nightclub trio with Holdt. Stuckenschmidt began composing music for the “masked dancing pair,” and this music consisted mostly of modernistic adaptations of the jazz and vaudeville tunes he performed in the nightclubs. Schulz and Holdt repudiated Schreyer’s Christian mysticism, for they regarded Christianity as a source of ecological degradation and diseased morality; instead, they followed their own, utterly personal ideology derived from Nordic myth, the Edda, an “Aryan” heritage of hardship, struggle against elemental strain on the body, and austere transcendence of physical and economic adversity (Chadzis 1998: 84-86). While they were never as constricting as Schreyer’s costume designs, the costumes constructed by Schulz and Holdt used materials—wood, metal, glass, canvas, heavy cloth—which made the movements of the performer stressful, perhaps even painful. The idea was to dramatize a primal conflict between the body and that which protects it and bestows identity upon what one might call its owner, although Schulz and Holdt approached this struggle with grotesque, perverse humor. They came up with bizarre names for the characters/costumes they invented: Springvieh, Technik, Bertchen, Bibo, Toboggan, Tote Frau. Each character entailed a unique movement style. Schulz and scholars of her work refer to her performance pieces as “dances,” but Schulz did not organize the pieces around steps or around any system of movement that would define the pieces as dances. She devised elaborate, cryptic notation maps for describing the movements of characters in the pieces, which were either solos or duets she performed with Holdt [Figure 139]. She used a different notation map for each piece, which makes it difficult to see how she employed a larger system of movement, even of her own invention, to create dances instead of pantomimes. Each costume/character represented for her a different notion of struggle between the body and the strange identity imposed upon it. She even sketched out plans for a “dance film” involving Springvieh and Toboggan and recognizably human figures (Chadzis 2006: 27).

However, because she drew and inscribed the notational maps so enigmatically, it is hard to determine well, if at all, how the performances worked as narratives. Hamburg reviewers tend to emphasize the “visionary” strangeness of the performance as a whole without clarifying its semiotic significance. But the expressionist artist and editor Karl Lorenz (1888-1961) vividly described the movements of Mann und tote Frau (1921), which featured both Schulz and Holdt:

This piece is the gloomiest [of the program], physically the hardest and the most charged. Suffering, heaving, tingling, confusing. A dying, but never an end to dying. Her body whirls, turns, waltzes, folds together. Exhausted?! Yes! But [the body] rises up again out of its exhaustion. She sets the movement again on its axis. She heaves, snorts, tortured, she winds again onto the floor. Dead? She stands up again high. She swells up. Stamping, snorting, grasping, curves, throws herself, hurls herself, pushes herself, torn, and: sinks, breathing in anguish, to the floor of Death?! She lifts herself yet again. Sorrow-whipped, tortured with pain, scattering snorts. She bores again into herself—into the accumulated sorrow, the wounded world-body. A bundel of woe thus surrounds her, a heap of pain, squelched, shattered, burned up in the painful world-view and: nothing dies, cannot die. Here at its darkest is the primordial origin of being (Chadzis 1998: 94).

Another journalist, the precocius Erich Lüth (1902-1989) in 1924 described Schulz’s movement aesthetic as follows: “Here creeps the body, its own presence lost within little houses of glass and wood, in rattling joints, in sharp edges, broad flat cases, which represent a strange projection of devious souls in dead things, which achieve their own fantastic-monstrous life, a quite ‘abstract organicity’” (Chadzis 1998: 92). With Skirnir (1921), a revision of Schreyer’s Skirnismol, an adaptation of a section from the Edda, Walter Holdt performed a solo pantomime in a dark, heavy, leather-metal costume with an enormous sword that transformed the Nordic-Viking warrior figure into a kind of grotesque robot (Chadzis 1998: 97-99). Schulz and Holdt represented the most extreme zone of expressionist pantomime, but they reached it at a huge cost. They were unable to live outside of their art and mythic vision, and they fell into abject poverty, for their productions never earned them any money on which to live. In 1923, Schulz gave birth to their son, which only exacerbated their financial and marital difficulties. Holdt refused to accept help from his family, who insisted he give up his artistic aspirations. But Schulz became impatient with Holdt’s lack of ambition while also fearing that he might abandon her. In June 1924, she shot him to death while he slept, then shot herself to death as she lay beside him and their one-year old son. Perhaps expressionism in pantomime could go no further than they took it, but no one since has gone so far in moving pantomime into an entirely new vision of the body’s power to metamorphose… into something inhuman, another species.

Expressionism in the arts exerted much appeal and influence internationally in the early 1920s, even if in Germany expressionist theatrical pantomime reached only a small, cultish audience. Thus in countries outside of Germany, artists could develop an expressionist pantomime aesthetic without experience of actual German expressionist pantomime performance. In Estonia, many artists nurtured an enthusiasm for modernist German culture, for Germans had a long and even dominant presence in the history of the country, and with the independence of the country from the Soviet Union in 1918, Germany seemed like a good friend to have in developing Estonia’s orientation to the West. German films and modern German plays in an expressionist style found a solid audience in Estonia (Epner 2015: 287-291). However, pantomime in the theater had almost no heritage; it remained confined, at best, to feeble employments of it in Russian-style ballet productions. Nevertheless, Estonia became the site of an extraordinary experiment in expressionist theatrical pantomime. August (Aggio) Bachmann (1897-1923), a government clerk, had since adolescence developed a passion for theater. He had no university education, but he studied business and languages at vocational schools. He had attempted to study acting in St. Petersburg (1917) and then in Tallinn (1918), but political circumstances prevented him from achieving this goal. He turned his attention to writing newspaper reviews of theatrical performances in Tallinn, but his interest in theatrical theory and his distaste for “frivolity” in theater (Offenbach) brought an end to his career as a journalist. The theatrical writings of Meyerhold and the German expressionist film The Cabinet of Dr. Caligari (1919) greatly inspired him and urged him to understand that “theater must be the form for new ideas” (Andresen 1966: 22-28). He may also have found inspiration from the Estonia Theater’s 1922 ballet production of Delibes’s Coppelia (1870), choreographed by the Bolshoi ballerina Viktorina Kriger (1893-1978). In this production, Kriger turned much of the ballet into a pantomime by using actors instead of dancers to perform roles, because the new ballet company did not have enough dancers with sufficient ballet technique nor could the dancers perform pantomime proficiently (Andresen 1971: 26). But Bachmann realized he would not have any kind of theatrical career unless he set up his own theater company. This he did in 1921, gathering together a group of young people to produce performances that occurred on Sunday mornings when the German Draamateater was free to him. The theater group therefore bore the name “Hommikteater” or “Morning Theater.” The first production was a staging of Der ewige Mensch (1919), an expressionist drama by Alfred Brust (1880-1938), a somber work on the theme of salvation in a time of religious disillusionment involving over a dozen characters and consisting almost entirely of dialogue. Although German theaters produced some of Brust’s plays with regularity during the 1920s, Der ewige Mensch (Igavene inimene) probably received its only performance through the Hommikteater. Bachmann decided he was better at directing than acting, and for this production he worked out every movement of a character’s action in relation to speech that each actor shaped according to a “melody” and musical dynamics. Each act unfolded according to a musically defined mood: act 1: andante; act 2: agitato; act 3: grotesque; act 4: philosophical (largo-allegro); act 5: andante. The act 3 “grotesque” entailed a rhythmic pantomime of masked city persons designated according to their social class (Andresen 1966: 30-41; Aaslav-Tependi 2012: 46-47). His next production, in 1922, was of the expressionist social drama Masse Mensch (1919) by Ernst Toller (1893-1939), a great but controversial work, in which a woman, Sonja (“The Woman”), sacrifices her marriage to an industrialist to support a strike by industrial workers and then sacrifices herself rather than join a Communist-controlled revolution, led by an alluring Nameless One, that requires the deadly sacrifice of others to achieve the utopian state. After the failure of the 1919 Bavarian Soviet Republic, in which Toller participated, the state of Bavaria banned any performance of Masse Mensch, but theaters elsewhere in Germany staged the play, which became throughout the world one of the most well-known and admired dramas produced by the Weimar Republic. In his production, Mass-inimene, Bachmann turned Toller’s “mass choirs” into movement choirs, who sang many of their lines and moved in a precisely choreographed fashion. He also used performers’ bodies as scenic objects and architectural structures. Hilda Gleser (1893-1932), already a prominent actress in the Estonia Theater, played The Woman in a starkly expressionist manner. (Bachmann was astonished that she desired to perform with the company.) For the dream sequence set in the stock exchange, Bachmann composed a pantomime set to a foxtrot with financiers in top hats accompanied by half-naked girls. The famous poet Marie Under (1883-1980), in an otherwise highly favorable, lengthy review, criticized the weak diction of the actors in some of the non-singing sections (Andresen 1966: 42-59; Under 1922: 151). For his next production, Bachmann drastically reduced speech in performance with his production of Walter Hasenclever’s Die Menschen (1919), translated as Inimesed. This radically expressionist, 5-act “dream play” dramatized the “journey” of a murdered man, Alexander, to understand why he “allowed” himself to be murdered. The very large cast includes the many people Alexander encounters in “the world today” who have in some peculiar, unintentional way contributed to his murder. The dialogue is very spare, mostly one or two-word phrases that characters blurt out without reference to what anyone else says, as if the characters hear only themselves. The play presents a society in which individuals remain so withdrawn into themselves, so isolated from each other, that they remain numb to anyone’s suffering, greed, or lust but their own. Throughout the play, Alexander carries a sack that contains his own head, given to him by his murderer. At one point, the head speaks one and two-word statements to Alexander. The only salvation in this dark, grotesque world is for the murderer to cry out, “I love!” With its many scenes and its montage organization of numerous social types, Die Menschen anticipates Hasenclever’s film scenario Die Pest (1920), discussed earlier. The only German production of the play took place in Prague in 1920, and it was not a success. Critics complained about the obscurity and aesthetic complexity of the work (Spreizer 1999: 82). The Estonian-language production in 1923 was the only other performance until the 1990 staging in Mannheim of Swiss composer Detlef Müller-Siemens’ two-act operatic adaptation. The play abounds in pantomimic scenes, but Bachmann, who played Alexander, treated the entire text as a pantomime to which he added some spoken words from the text. The effect was like watching a silent film punctuated by cries. Bachmann made imaginative use of new spotlights installed in the Estonia Theater, and he divided the stage into three sections to allow for swift shifts from one scene to the next. He individualized each of the socially defined characters by assigning them a distinctive movement, with Alexander making very soft, lilting movements that served as a kind of default kinesis against which the movements of all other characters deviated or contrasted. Under Bachmann, the Hommikteater had become a socialist organization; the programs for the company did not even list the persons involved with the productions. With Inimesed, the company had created a pantomime that was an intense critique of social pathology, a pantomime that depicted all classes of society as implicated in the murder of an individual, in the suppression of love, and in the awakening of murderous impulses. No other pantomime of the era attempted to represent on the stage such a wide range of social types, nor did any other pantomime project such an overt political attitude without sinking into propaganda. Perhaps only an amateur company could adopt such a sophisticated political approach to pantomime. Again, Marie Under wrote a glowing review of the production, and the company seemed poised to become a significant artistic power within the small country (Andresen 1966: 60-68). Unfortunately, Bachmann suffered from heart disease and tuberculosis, and he died shortly after the production of Inimesed at the age of twenty-six. The Hommikteater attempted one more production, in 1924, an adaptation of a 1906 Symbolist play by Valery Bryusov, Maa (Land) directed by Hilda Gleser, who emulated Bachmann’s theory of extravagantly stylized expressionist bodily movement contrasted this time with scenes of the poet’s words spoken in darkness. But with the death of Bachmann, the company lacked a cohesive sense of purpose and ceased to exist after Maa. Alas, the approach to pantomime taken by Bachmann did “not find followers in Estonia or elsewhere” (Andresen 1966: 88). Bachmann was a visionary artist who could create distinctive, politically inflected pantomimic action because he did not really apply any sort of pantomime technique: each production entailed a different working out of pantomimic action. He was not a teacher, for teachers learn a technique that they teach to others. After his death, it was not enough for Bachmann to function as a model of brilliant artistic imagination; to have “followers,” he had to leave behind a pantomimic technique that could be replicated and applied to one production after another. But the problem was not that Bachmann did not live long enough to have “followers”; the problem was that Estonia, like other countries, did not produce more artists with his unique, passionate, self-educated pantomimic imagination.