Pantomime: The History and Metamorphosis of a Theatrical Ideology: Table of Contents

PDF version of the entire book.

The Silence (1963)

In the postwar era, motion pictures have shown greater propensity than theater to explore the possibilities of pantomimic action, particularly since the 1960s, when the film industry internationally made a concerted effort to free itself from the excessive reliance on talk that dominated filmmaking in the 1940s and 1950s. Movies anyway often contain actions in which characters do not speak, and the screen time for these actions increased considerably from the 1960s onward, although the purpose of these actions was seldom to focus the viewer’s attention on how actors performed them or to make unspeaking actions the subject of cinematic narrative, and the postwar film industry has never believed that the artistic or financial value of films would expand if they contained no voices at all. Even so, films have appeared, largely in a comic vein, that consist almost entirely of pantomimic actions, such as the comedies Mon Oncle (1958) and Playtime (1967), directed by Jacques Tati (1907-1982), the Mr. Bean films (1997, 2007) and television show (2002-2004; 2015-2016) produced by and starring the English comedian Rowan Atkinson (b. 1955), or The Artist (2011), directed by Michel Hazanavicius (b. 1967), a black-and-white film that strives to emulate qualities of silent films in the late 1920s and depicts the relationship between a Hollywood film star and a young actress during the period when movies transitioned to “talkies.” The American independent film Trapped by Mormons (2005), directed by Ian Allen, was another black-and-white effort to reproduce the qualities of a silent film from the 1920s by having the story take place in the 1920s, and Allen modeled his film after the English silent film melodrama Trapped by Mormons (1922), directed by H. B. Parkinson (1884-1970). Both The Artist and Trapped by Mormons associate cinematic pantomime with silent film and not with the time in which the films were made: pantomime signifies an “old” way of acting, it evokes a nostalgic mood, or, as in Trapped by Mormons, it affirms a “camp” pleasure in celebrating unfashionably extravagant, melodramatic action. The Canadian director Guy Maddin (b. 1956) has also appropriated silent film gestural tropes in films like Tales from the Gimli Hospital (1988) and Archangel (1990), always for a comic or “camp” effect, but he tends to integrate bodily actions into montage imagery that relies on many editing and photographic processes: pantomime does not construct the narrative; rather, the narrative consists of complex images that reference silent film poses and gestures in the desire to create a dreamlike, mythic vision that is also “old,” an element of cinematic consciousness whose “kitsch” style still exerts an appeal for “our” time.

A more “serious” approach to pantomime in film entails pantomimic action that the filmmakers do not build around the unique skills of a particular actor to perform gags, slapstick, or stunts or around a director’s unique skill at visualizing a narrative. That is, the pantomimic action is unique to the narrative and its characters, and different actors and directors will perform the pantomimic action differently. The pantomimic action constructs a narrative that is larger, so to speak, than any interpretation of it or even the medium of interpretation. The literary imagination is the primary source for such narratives. Directors like Tomaszewski and Mackevičius created powerful pantomimes inspired by literary works their authors never considered as pantomimes. Since the end of the silent film era, however, filmmakers have shown little inclination to construct narratives out of pantomimic action, for this would involve building sequences of physical actions related to the theme of the body’s detachment from speech, to what the body “says” rather than what the performer or director “says” in performing them. The pantomimic imagination is a vision of how bodies signify uniquely in relation to a theme in which speech is an unhelpful distraction, if not an ailment—but rare are the filmmakers with an interest in this theme. That is to say, the pantomimic imagination is the subject of the film—the sequence of physical actions is in the story, not in the screenplay or film, although these may include pantomimic action in their adaptation of the story. Directors, however, may possess literary imaginations insofar as they are authors of stories and think pantomimically in constructing their stories.

A good example of this “serious” approach to cinematic pantomime is the 1963 Swedish film The Silence (Tystnaden), directed by Ingmar Bergman (1918-2007), who shot the film in September 1962. Although he is famous as a film and theater director, Bergman also wrote plays, short stories, and novels as well as the screenplays for all the films he directed and screenplays for films directed by others. He possessed a literary imagination in that his way of seeing of the world, his “stories,” entered his mind at a level above their realization in a particular medium. The Silence is not a pantomime film like The Artist. The film contains brief passages of dialogue, but these bear directly on the theme of “silence” accompanying the actions of the characters, and Bergman himself, though proud of the film, later concluded that much of the dialogue was “unnecessary” (Bergman 1994: 109). While making The Silence, Bergman kept a notebook in which he self-consciously described his efforts to make a film that did not rely on speech. He described his own films as suffering from what he called “dialogue disease.” “I have to curb my delight in [writing] dialogues. […] But how… incredibly dependent one has become on talking. Now I work with one arm tied [behind my back]. I really, once and for all, have to get away from dialogues. I’m damned tired of all these meaningless words and discussions. Besides it’s very hard finding oneself mute. Given that all my life I’ve practiced [writing] dialogue, it certainly gives you a sense of loss and anxiety not to be allowed to use it anymore.” Thus, in the film, “the dialogue [should be] only a rattle on the soundtrack without any meaning. Ignoring all that talk will be delightful…[and] cinematographic” (Koskinen 2010: 70-71). The film is important because it makes imaginative use of pantomimic action in relation to narrative and because it makes innovative use of pantomimic action in relation to cinematic devices. The entire story transpires over a period of a little more than 24 hours in an imaginary European country whose language is unintelligible to the main characters: two sisters, Anna and Ester, and Anna’s young son, Johan. Because Ester suffers from a mysterious illness, perhaps tuberculosis, the trio interrupts their train ride to Sweden to stay in the city of Timoka until Ester is able to continue the journey. They stay in a huge, luxurious, but mostly empty hotel. An intense heat wave oppresses the city. While Ester lies in bed, Anna takes a bath and asks Johan to scrub her back. Mother and son then take a nap, as Ester tries to work at her typewriter in bed. But a powerful feeling of loneliness overwhelms her, and she masturbates to alleviate her agitation. When Johan wakes from the nap, he leaves his mother sleeping and wanders alone through the corridors of the hotel and encounters different persons, including a troupe of Spanish dwarves, who invite him into their room, put a dress on him, and entertain him until their leader arrives and puts an end to the revelry. In the hotel room, Anna wakes and changes into a clean dress. She tells Anna she is “going out” and leaves, but Ester again becomes agitated by a feeling of abandonment and collapses with fear that she will die before reaching her homeland. She rings for the elderly hotel servant, who lifts her into bed and calms her through a series of comforting actions. In a café, Anna sits at a table, smokes, orders a beverage, and buys a newspaper written in the language of the country. The waiter performs several actions indicating his sexual attraction to her, but they do not exchange any words. Johan returns to the hotel room, and Ester invites him to eat some of the food the servant has brought. She tells him the good things that will happen to him when he reaches home, but he prefers that she not touch him. He goes into an adjacent room to draw a crude picture of a human face. Anna visits a theater, and from a balcony seat, watches a clown tumbling act performed by the Spanish dwarves. A man and a woman in seats near her engage in sexual acts that horrify her, and she leaves the theater. After some hesitation on the street, she returns to the café and gives a subtle, wordless signal to the waiter. Johan wanders the hotel corridors again and encounters the elderly servant eating his meal. The servant shares a piece of chocolate with Johan and shows him some photographs apparently of his family decades earlier. When Anna returns, Johan leaps to greet her; she enters the room, but Johan remains in the corridor and hides the photographs under the carpet. Anna changes into a bathrobe, washes, as Ester, elegantly dressed, watches her, then returns to her writng desk. Anna approaches her and warns her to mind her own business, which leaves Ester tense. In the evening, Ester, in pajamas, listens to Bach on the radio, while Anna, in another dress, holds Johan in her arms. The servant brings coffee to Ester, and she asks him the word for music. He replies with a word that is similar to music. “Bach” is another word they share. After Johan leaves to wander the corridors, Anna and Ester converse in the shadows of the room. Ester asks where Anna went in the afternoon, and Anna delivers a story that is a lie, an account of a sordidly promiscuous sexual encounter with a man in a movie theater. But after Ester wonders if the story is true, Anna admits she lied. Ester does not want Anna to go, and she physically discloses an erotic, homosexual desire for Anna, who repulses her: “I have to go.” In the corridor, she encounters the waiter. They enter another room, secretly watched by Johan from the shadows of the corridor. Johan returns to his room, where he sees Ester sleeping. He watches a tank rumble through the street below, recalling the scene in the train carriage when he saw another train carrying many tanks. Ester awakes and asks him to read to her, but he instead puts on a Punch and Judy puppet show, in which the characters speak an unintelligible language. In the other hotel room, Anna and the waiter lounge in speechless post-coital anticipation of further sex. Ester works again on her translation and Johan asks why she translates books. He asks also if she knows the language of the country they are in, but she says she only knows a few words. He then asks her to write down the translations of the words. Ester learns from him that Anna is in the other hotel room. Anna complains about Ester to the waiter, who understands nothing and says nothing. She hears Ester calling, weeping. Anna opens the door, Ester sees Anna in the arms of the waiter, and sits at a table in dismay, wondering why Anna torments her. Anna gives an accusatory speech in which she condemns Ester’s “egotistical personality”: “You can’t live without feeling superior.” Ester denies the accusation, and claims that she loves Anna. “Poor Anna.” But Anna can’t stand the patronizing tone and orders Ester out of the room. But Ester repeates: “Poor Anna,” caresses Anna’s hair and leaves. Anna laughs, then starts crying, as the waiter initiates another coital session. In the corridor, the troupe of dwarves returns from the theater in their strange historical costumes; they nod to Ester standing alone in the corridor. In the morning, Ester leaves the waiter sleeping, but when she opens the door, she finds Ester slumped against it. With Ester in bed again, the hotel servant helps her drink some juice. Anna informs her that, after a snack, she and Johan will leave on the next train. Johan and Ester say good-bye. Through gestures, Ester asks the servant for her writing tablet. But she soon begins talking to the uncomprehending servant, explaining that, “It’s all a matter of erectile tissue and secretions. […] I stank like a rotten fish when I was fertilized. […].” With her hand gently resting on the servant’s head, she says “I don’t want to accept my wretched role […], submission to “the horrible forces […] of ghosts and memories. […] All this talk. There’s no need to discuss loneliness. It’s a waste of time.” “Feeling better,” she speaks fondly of her father. But she suddenly becomes wracked by another seizure, gasps desperately for air: “Must I die all alone?” An air raid warning sounds. She calls for her mother. Johan returns and approaches the bed. Ester tells him not to be afraid. “I’m not going to die.” On the train leaving the city, rain pours against the carriage windows. Johan pulls out the “letter” Ester gave him with the words translated from the language of the foreign country (actually a language invented by Bergman). He shows it to Anna. “Nice of her,” she says. She opens the carriage window to let the rain fall on her. The final shot is of Johan’s face reading the words Ester has translated.

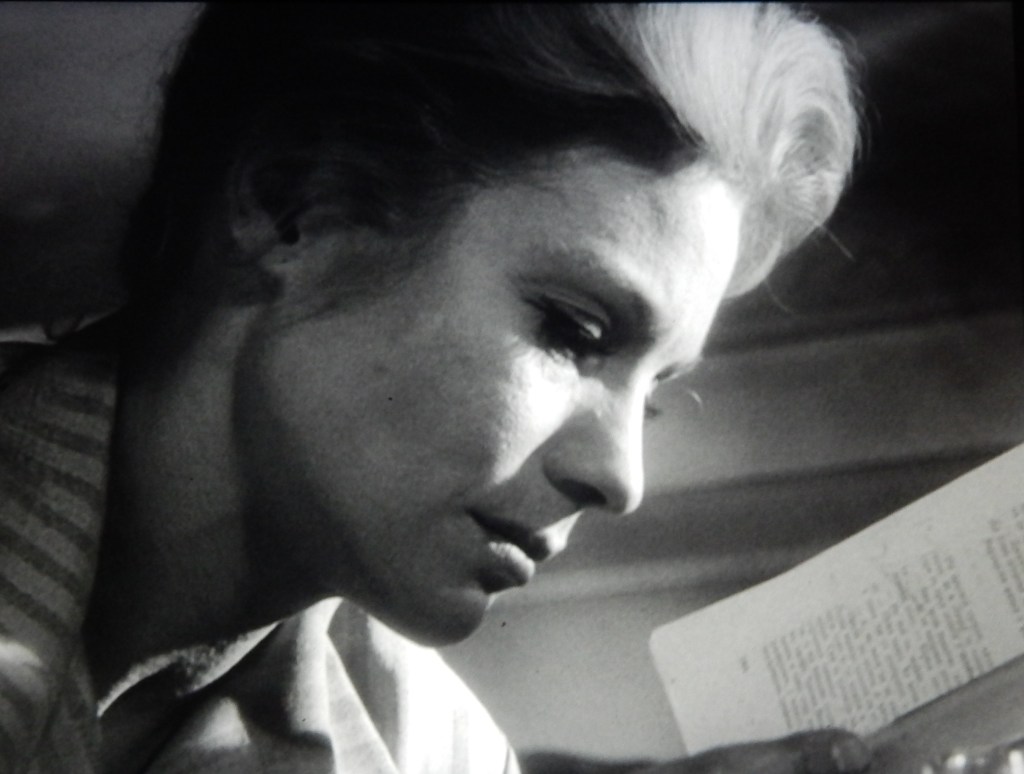

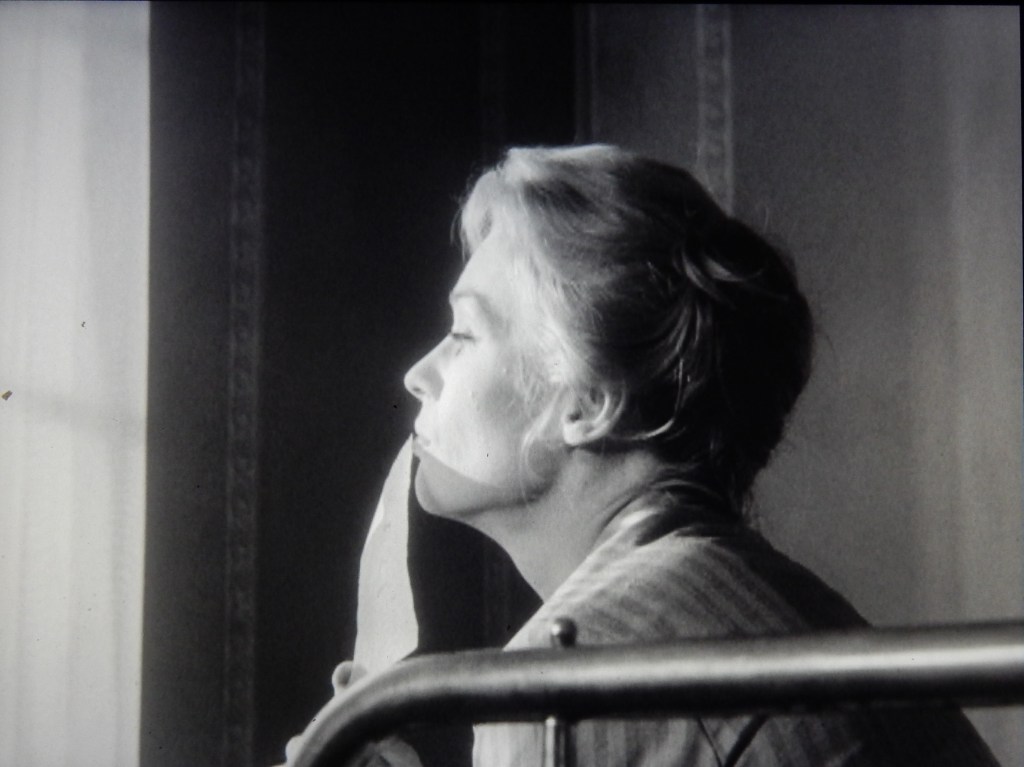

This account of the story leaves out many actions and details that construct the narrative pantomimically and cinematically. For example, in the opening scene set in the railway carriage, pantomimic action alone reveals a variety of details about the relationship between the three main characters and their status as foreigners. That Anna and Ester are sisters seems communicated by placing the two women next to each other rather than facing each other and having Johan sitting beside Anna, although none of the characters actually looks at any other until quite a bit into the scene. The heat is intense and signified by the listlessness of the two women: Ester, played by Ingrid Thulin (1926-2004), drowses, while Anna, played by Gunnel Lindblom (1931-2021), gazes blankly into space, as if recalling something very remote. The scene also shows that Anna has a very close, loving relation to her son, played by Jörgen Lindström (b. 1951), who is about ten years old: when Anna moves to the other side of the carriage to doze, Johan follows and presses his head against her breast; she strokes him, urges him to curl up and sleep next to her as she places a protective hand on his shoulder while gazing again into space until, for the first time she directs her gaze toward Ester. Ester is sick: she suddenly starts suppressing a cough and breathing heavily; when Anna moves to comfort her, Ester resists and leaves the cabin. Ester brings her back and lays her on the seating bank. Costumes convey some of the upper class status of the women, who, after all, travel in a first class carriage: Ester in a pale business suit; Anna in a sleeveless white dress and a necklace made of thin gold rings. But the two women also disclose an elegant physical composure associated with their class, which, however, does not disguise fundamental differences between them: Anna is more restless and outward looking, shifting from one seat to the other. She likes to display herself, whereas Ester is more withdrawn into herself, turns away when she coughs, and tries to hide herself. Anna is more physically demonstrative, touching herself, touching her son, and touching Ester. Johan is like his mother: restless, but exhibiting a curiosity about the environment that the women do not share. In the only dialogue in the entire train carriage scene, which is seven minutes long, he points to a sign in the train and asks Ester: “What does it mean?” To which she responds: “I don’t know.” He pronounces the unintelligible words. When Anna shuts him out of the cabin to attend to Ester, he wanders down the corridor, gazes out the window as the sun rises over mountains, but when he slumps down to the floor to sleep, the train conductor enters to announce that the train is stopping soon at Timoka, although the viewer cannot understand his short declaration. Johan peers into a carriage cabin and sees military officers awakening, but he does not want them to see him. He finds another place in the corridor to sit and look out the window as the train enters the city. He sees the train carrying the tanks moving in the opposite direction, creating the impression of entering a country facing a conflict that words may not solve. As he gazes out the window at the strange city, his mother comes behind him and they both stare out the window intently, but Gunnel Lindblom gives Anna a wary, hawk-like stare that contrasts with Johan’s wondrous gaze and fixes Anna with a “hardness” lacking in Ester. The entire railway carriage scene presents characters inhabiting a world of “silence,” in which they prefer not to talk, prefer to communicate through subtle bodily gestures, because silence creates greater or enough closeness between people than speaking.

At the same time, though, silence creates a space between the family members, silence makes them seem alone, solitary. This silence is not oppressive; rather, it fuels a tension, an anticipation, an expectation, a sense of entering a “foreign” domain of the self. Despite the seemingly cramped setting, Bergman creates a powerfully dramatic atmosphere in which speech is “unnecessary” and would merely amplify the oppressive heat. Speech would intensify an oppressive atmosphere of confinement, as indeed it does in the later hotel room scenes. It is words that cause a fatal sickness and apparently contribute to the translator Ester’s illness: she starts coughing after Johan asks her what the railway sign means. The scene invites viewers to look at the characters without spoken “explanations,” without talk that identifies where the characters are coming from, why they are together, why the boy has two “mothers” and no father, or where they are going. The idea is to see the characters free of any language that would frame them within a “motive” that clarifies why the viewer is watching them. The viewer watches them to see how “silence” keeps them together. The camera constructs the viewer’s perspective on the pantomimic action in an innovative way, and the cinematographer, Sven Nykvist (1922-2006), obviously contributed to the innovation. In the cabin of the railway carriage, the camera, in mid-shot, pans from one character to another or characters move toward or away from the camera to emphasize the space between the characters; the camera avoids point-of-view shots or even cuts, except when Anna casts a dark stare at the dozing Ester, who suddenly begins coughing. The viewer sees the action as if sitting where the window is between the two seat banks, which creates a sense of closeness to the characters without being certain whose point-of-view is in control of the narrative. When Johan enters the corridor of the railway carriage, Bergman employs more shots and a great variety of camera angles, including point-of-view shots for Johan when he sees the sun rising over a mountain ridge, looks into the cabin with the awakening officers, and watches the tanks racing by on the opposing train. In a couple of angles, the camera looks at Johan gazing through the window from outside the window. Nykvist uses heavily expressionist lighting to show Johan moving in and out of shifting shadows, but, as always with Bergman, the lighting gives Johan’s face a soft luster against dark backgrounds. Yet these corridor actions do not establish Johan as the protagonist of the narrative nor even that the narrative issues from his point of view. That is clear from the powerful shot outside the window of Anna looming hawk-like behind the rapt Johan as the train arrives in the city: they gaze outward in the same direction, but the image shows that they have quite different points of view that neither “knows.” The film never does settle on a dominant point of view, for the point of view shifts back and forth from Anna to Ester to Johan to show how, despite their closeness, each lives separately and unknowingly from the other. Johan is, so to speak, “between” the sisters: he loves Anna and Ester, and they both love him; Ester feels a deep attachment to Anna, but Anna hates her sister and achieves her freedom from Ester only by abandoning her. No point of view can prevail when neither the boy’s love for the two women nor their love for him makes it possible for them to love each other. Pantomimic action best represents Bergman’s perception that love precariously binds people together through “silence”—that is, a condition of doing things together, of traveling together, of living together, in which it is not “necessary” to speak to signify the presence of love. Words, especially speech, invariably undermine this precarious balance “between” love and hate. Yet Ester’s work as a translator, Johan’s curiosity about the meaning of the words in the foreign country, and Ester’s “letter” to Johan translating the words she has learned from the servant imply that less precarious expressions of love might happen by communicating in another, “foreign” language, although Anna, responding with a tepid “That’s nice” and a dismissive gesture, seems skeptical [Film Series B].

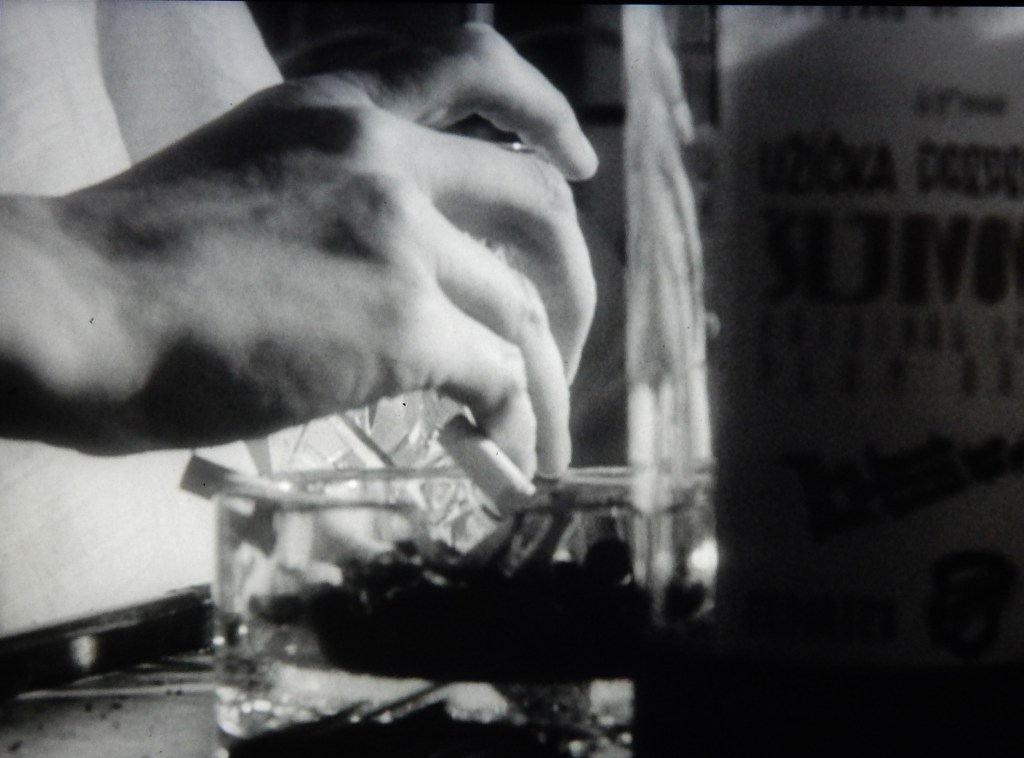

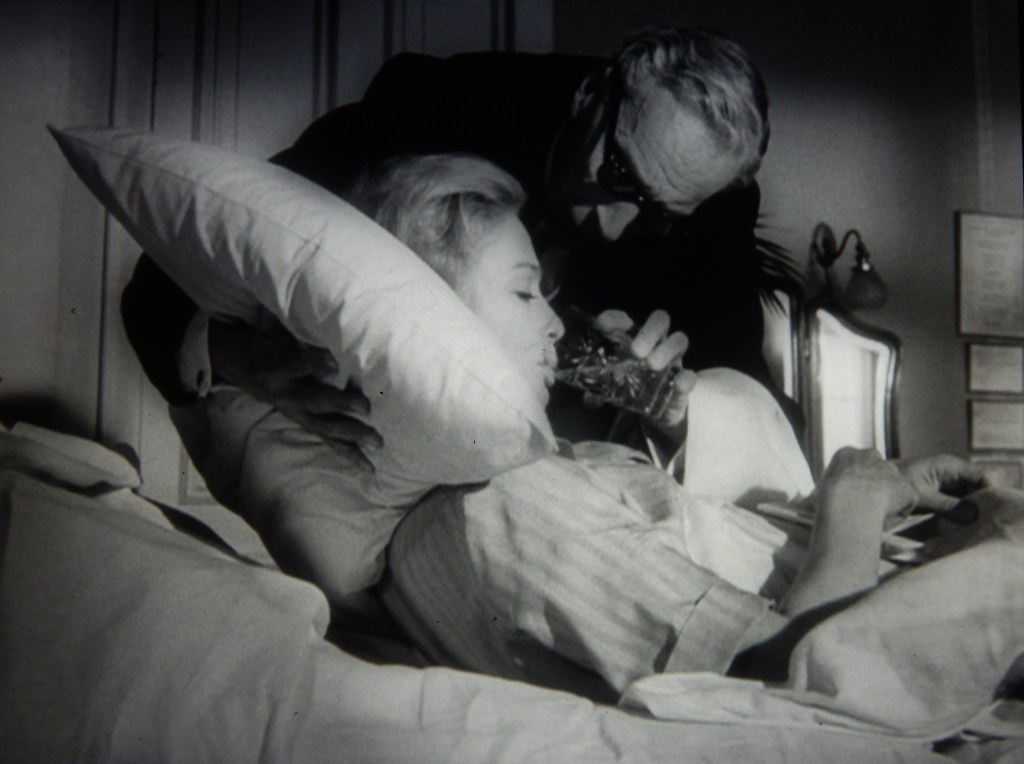

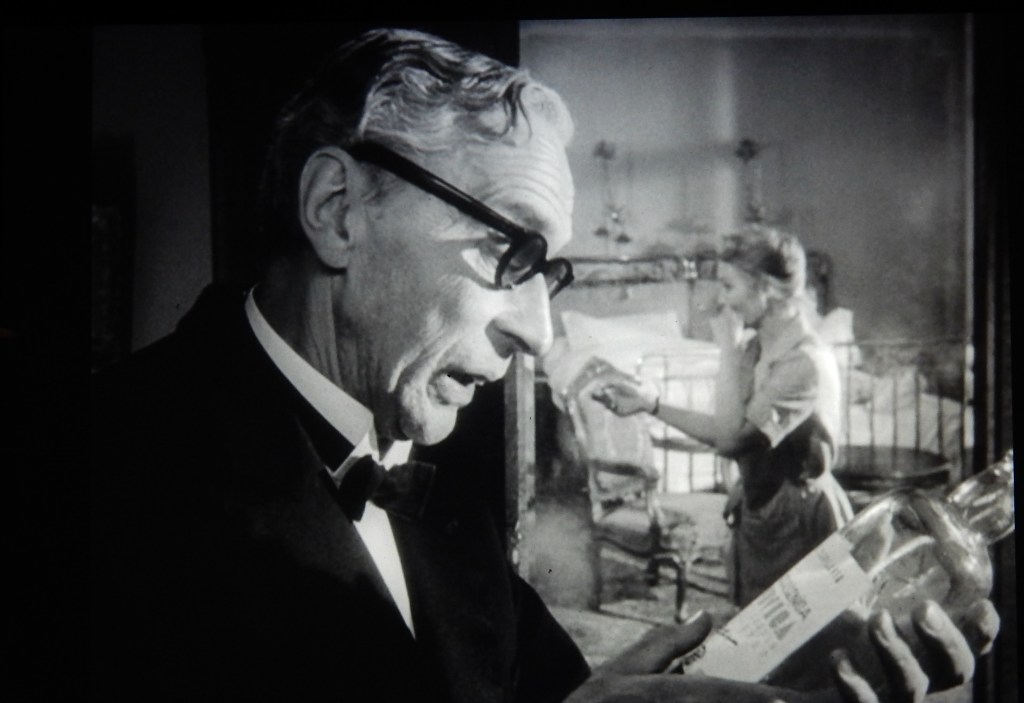

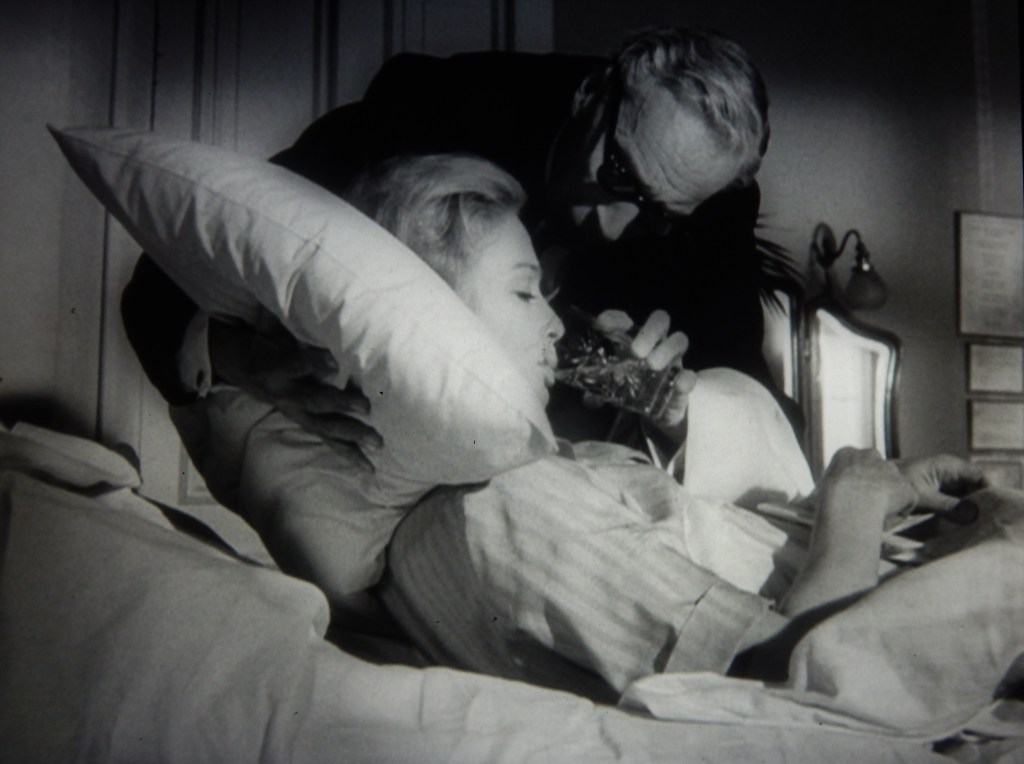

Of course, the film goes on to present many more scenes of imaginative pantomimic action in combination with innovative, cinematic ways of seeing pantomimic action. After Anna and Johan get into bed to take their nap, the camera focuses on Ester as she works in bed in her pajamas, reading, notating, coughing, gasping, smoking, and drinking. The camera, at low angle, pans from her face to her hand and watches her hand, stub out a cigarette, pour a drink, turn on the radio, tap to the music, and change the channel, as her head comes into view, pressed against her hand on the radio. The camera follows her head as she lifts herself upward and seems to inhale the serene music, causing her to smile, before returning to her book and pen. But she can’t concentrate. She wanders, smoking, toward the doors leading to the room inhabited by Anna and Johan, but the camera does not follow her; it watches her recede and actually tilts down to show her receding figure obscured by the bed covers and the radio. On the other side of the door, the camera watches Ester from a higher angle as she approaches the bed and studies the sleeping pair; she leans against the bedrail, lightly touches Anna’s hair, considers touching Johan but hesitates, then leaves them. It is a pantomime of small, subtle gestures rendered intimate by the camera’s closeness to the performer. When she returns to her room, the camera follows her face in profile as she smokes, deeply melancholy, and moves to the window to gaze down into the busy street, with the film cutting to a view of her from outside the window. She sees a wagon pulled by an emaciated horse roll into view, although buses and cars also crowd the street. An old man in a black derby drives the wagon, stops it, and gets down. The wagon is full of furniture, plants, and strange, unidentifiable objects. Perplexed, Ester returns to her bottle, turns off the radio, pours another drink, which empties the bottle, the camera panning up from the little table to her face. The camera then pans from her face to the servant (Håkan Jahnberg [1903-1970]) entering the room and holds on his profile as Ester, also in profile, appears, full figure, reflected in the full length mirror behind him, so that she seems further away from him than she actually is. She asks him in French, English, and German if he speaks any of those languages, but he politely indicates he does not. She therefore mimes that she would like another bottle of liquor. He understands. She sits down and lights another cigarette, with the camera again studying her profile, her exhalations, her desire for some sort of voluptuous pleasure, as the camera moves closer to her face, while an air-raid warning signal sounds in the distance. The servant places a tray with a glass of brandy and a bottle of it before Ester, who savors the aroma from the glass and examines the bottle. She offers the servant a cigarette, but he refuses, as the camera now shifts to a low angle shot behind her to observe him. She gestures for him to tell him the word for “hand” in his language, and he responds by speaking the word and writing it on a piece of paper. The bell rings summoning him to another room, and he gestures that he must run off. She studies the piece of paper, pronounces the word, then grabs the bottle of brandy as the camera follows her back to the bed, where she drinks and caresses her lips with the paper. She falls back onto the bed, while the camera watches her from above as she unlooses her her pajama top, caresses her breast, opens her legs, and inserts her hand into her pajama pants to masturbate with her eyes closed. The camera moves in on her face; at the moment of orgasm, her eyes open wide as she gasps. She closes her eyes again and turns into the billowing comforter to sleep as the sound of jets suddenly roars overhead. The entire scene is rich in captivating pantomimic action that dramatizes Ester’s loneliness, her gathering anxiety about being excluded from the sleeping pair in the next room, and her sense of being excluded from the strange, foreign culture in the street below her. But the scene also reveals her sensuality, her pleasure in voluptuous sensations, quite in contrast to the image of primness she projected in the opening scene, although these become entangled with self-destructive addictions. She makes the camera look at her from different angles and move toward and around her, as if searching for a way to stabilize its view of her. It is an astonishing sequence of physical gestures and actions that exposes the basis for the woman’s deepest anxiety: that she has not been loved as she has deserved nor has she been allowed to love as fully as she is capable, the most powerful cause of loneliness. Ingrid Thulin performs this melancholy sequence with a confidence that is riveting, as if she felt completely at ease and lilted by the character’s sorrow, utterly fearless at incarnating Ester’s intense vulnerability and intelligence. Bergman himself remarked that making the film was an “enormous amount of fun” because all involved with the production felt “uninhibited,” and the actresses were “always in a good mood” in relation to performing quite daring scenes, although Gunnel Lindblom did insist on some inhibition when she refused to perform a scene with the waiter in the nude (Bergman 1994: 112; Lindblom 1995: 62). Indeed, it is doubtful that pantomime as precise, imaginative, and uninhibited as appears throughout the entire film could happen without a profound sense of trust between the director and the performers: this sort of elegant, “uninhibited” pantomimic action is possible when the performers and film crew know each other so well from their extensive previous work together without necessarily “knowing” the characters well at all. The characters take the performers into an unknown region of humanity that requires a lack of inhibition, but ironically, this lack of inhibition depends on a fundamental condition of trust between people that the film itself neither refutes nor treats as a salvation (cf. Fischer-Kesselmann 1988).

In subsequent scenes, however, the film explores aloneness from different perspectives: being alone without being lonely. When the jets roar overhead, Johan awakes. He leaves his mother sleeping and, with his toy pistol, he wanders through the cavernous hallways of the hotel, firing his pistol at a service worker changing a lightbulb in a chandelier, watching the elderly servant in his tiny office and running away from him when the man approaches him, observing a huge erotic painting of a centaur grasping a nude woman, running away again from the grasp of the elderly servant, casting his distorted shadow against the wall of a stairway, and coming upon the open door to the room with the troupe of dwarves, all male, who silently play cards, read, drink, smoke, or mend costumes. Johan shoots two of the dwarves and a third wearing a lion’s costume, and they play with him by pantomiming their deaths. The raucous, but wordless dwarves put the dress on him and entertain him with one of them leaping up and down on a bed wearing a clownish gorilla mask until the apparent leader enters and orders them to cease, though he graciously escorts Johan out of the room. In a corner, Johan pisses on the floor, then walks away whistling, as if whistling negates his bad behavior. A homosexual aura pervades the old servant’s affection for the boy and the dwarves’ invitation to him to join their strange, foreign society, dramatized so well by the wonderful close up shot of a dwarf’s hand beckoning Johan to enter the room. Johan clearly enjoys being alone; the hotel offers happy opportunities for adventure, and he finds pleasure in the freedom of speechless wandering.

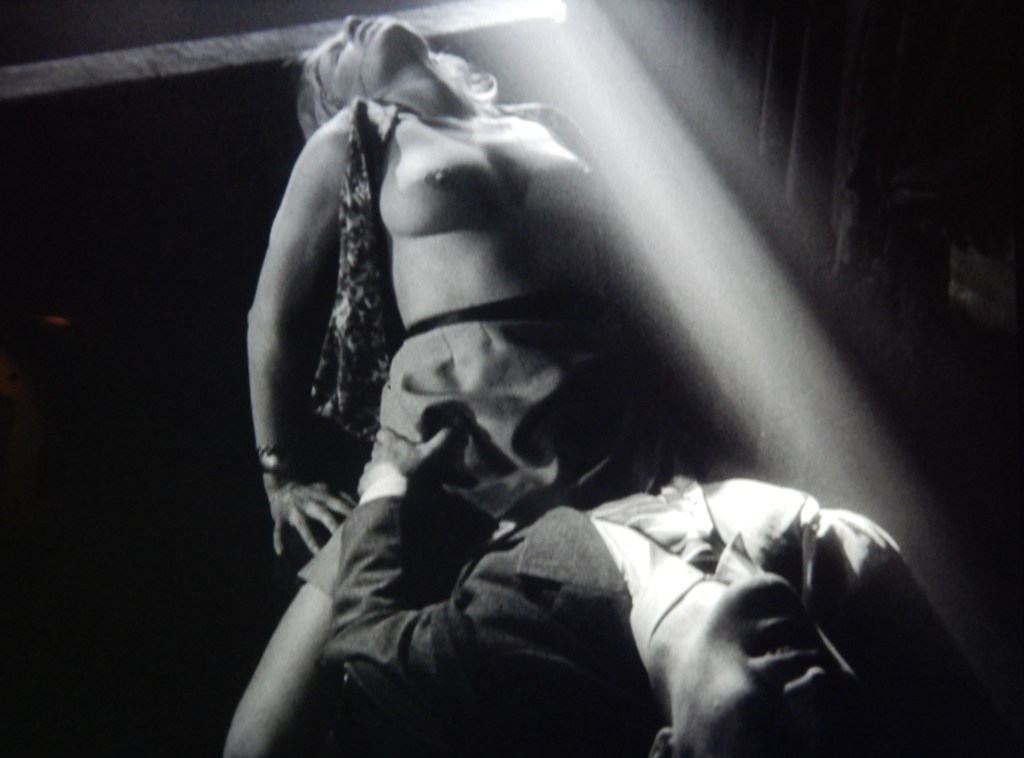

But Bergman intercuts the scenes of Johan exploring the hotel hallways with the scenes of Anna washing and getting dressed to go out and, after Anna leaves, of Ester’s despair, collapse, and return to bed with the kind assistance of the elderly servant. The intercutting implies that the contrasting conditions of solitude experienced by Ester, Johan, and Anna are dependent on each other—that is, on causing Ester’s loneliness, on one person abandoning another, as, in a small, “innocent” way, Johan has abandoned both women. But he returns to Ester, and she shares her dinner with him as she explains his future when he returns home, where his grandparents will take care of him. The film then focuses on Anna’s solitary visit to the café, her silent interaction with the waiter, played by the longtime Bergman actor Birger Malmsten (1920-1991), her entrance (wearing dark glasses) into the Variete Theater, where, smoking in the shadows, she watches the dwarf tumbling act and the couple near her engaging in sexual intercourse partially in the glow cast by a spotlight. The super-expressionist lighting amplifies Anna’s horrified stare at a couple utterly shameless (or “uninhibited”) in succumbing to their lust. She is a person who lives in shadows. Later, when she enters the hotel room with the waiter, she commands him not to turn on the lights. Yet when Ester comes into the room, Anna turns on the lamp, so that Ester feels humiliated by Anna’s shamelessness in cavorting with the nude waiter in bed. When Anna leaves the theater, she enters the sunny street crowded entirely with men—soldiers, workers, students, pensioners, and professionals, although a few women sit outdoors at the café when she returns to give the waiter an almost invisible signal to rendezvous. The camera follows her with a telescopic lens to produce a surveillance mode of viewing and to imply that she is moving in a society that does not encourage speaking. Indeed, in the café, in the theater, on the street no one is seen speaking and no voices are heard, although the street is noisy with activity. Bergman then cuts to Johan wandering through the hotel again holding his pistol. He watches the elderly servant in his office eating and drinking with quietly ritual deliberation. When the servant notices Johan smiling at him, he performs a miniature puppet pantomime using a sausage that he then swallows. Seeing that Johan has not enjoyed this cannibalization of the sausage character, the servant offers to share with him a chocolate bar. Johan sits beside the servant, munching the chocolate as the man pours himself a drink, swallows, and sprinkles Johan’s head with droplets, which causes Johan to smile with amusement, although nothing the man has said is intelligible. The servant then pulls from a large wallet the photographs that apparently depict his parents and what appears to be an outdoor family funeral ceremony long ago. He puts the photos in Johan’s hand and puts his arm around the boy, and with his face conveys a profoundly sorrowful sense of his own loneliness. But Johan hears the sound of his mother entering and runs off to greet her; she fondles him, but they do not speak as she opens the door to the room. Left alone again in the corridor, he studies the photographs before slipping them under the carpet. Perhaps with this mysterious action, Johan hopes to “bury” the memory that binds him emotionally with the old servant, as if loneliness were contagious, an illness, such as already afflicts Ester.

The Silence contains numerous other scenes of comparably imaginative pantomimic action, which fascinate viewers because of the unusual ways the camera sees the action. It is pantomime designed for a motion picture camera capable of a highly dynamic relation to the performers, capable of observing subtle inflections of gesture, and capable of interweaving separate pantomimic sequences into a larger “view” of the semiotic relations between bodily actions performed by people when they are alone. Bergman showed how film technology widened the meaning of “pantomime” and expanded the expressive power of the body to communicate large ideas when speech has lost its authority to control the narrative. It is an “uninhibited” form of pantomime insofar as Bergman completely trusts his actors to perform “natural” actions and avoids stylized movements that treat the body as an abstract form rather than as an instrument of consciousness in material reality. The film does not even employ any soundtrack music to accompany the pantomimic action. All music in the film comes from sources within the image, such as the radio, the jazz vibraphone in the café, and the pit orchestra in the Variete Theater. In the evening, in the shadowy atmosphere of her room, Ester listens to the radio play a Bach cembalo prelude while Anna holds and embraces Johan on her lap in the room behind Ester. The servant enters bringing coffee, and Ester asks him the word for “music” in his language. He replies with a very similar sounding word. Ester says, “Sebastian Bach,” and the servant repeates the name, nodding his familiarity with the name and the music. A few moments later, after Anna asks to borrow cigarettes from Ester and Ester suggests that Anna and Johan leave this evening, Anna asks what the music is, and Ester replies, “Bach. Sebastian Bach,” to which Anna replies, “It’s nice.” Ester turns off the music, which soon precipitates the quarrel between the sisters over Anna’s appetite for promiscuity and their competitive relation to their father. It is as if music was a translation of a foreign language that otherwise no human understands. But the music is not an accompaniment to pantomimic action; it is a peculiar intrusion upon the “silence” that is the default accompaniment to this “natural” performance of pantomimic action [Film Still Series B].

This “uninhibited” mode of pantomime caused enormous controversy from the moment The Silence premiered in Stockholm in February 1963. Bergman believed that the film would not attract any audience, and Svensk Film Industri, believing the project was too obscure, originally did not want him to make the film, but he went ahead with it anyway, an act of great confidence and courage (Sima 1970: 195). The Silence, however, became the most successful film in the history of the company, and in West Germany it was the most successful film since 1955, with eleven million viewers (Schmitt-Sasse 1988: 17). Of course, the boldness of the sex scenes startled many viewers around the world, but this boldness was perhaps unthinkable without a new way of seeing the body, without seeing the body as a thing in tension with the voice trying to control it, as a thing that made speech “unnecessary” or an encumbrance to knowledge of others. The film precipitated an immense amount of discourse that contended or merely insinuated that the “silence” referred to the absence of God in the modern postwar world, because the narrative contained so many actions “free” of any voice contextualizing them within a morality encoded through language (cf. Theunissen 1964; Schmitt-Sasse 1988). Pantomime elevated the power of film technology to see humanity without much, if any, deference to Christian morality. For this reason, the pantomimic action of The Silence signified for many people a dangerously radical image of the body: with voices largely absent, “naturally” performed actions, rather than stylized movements, appeared intensely mysterious without evoking a religious aura, like translating from a foreign language, producing a disturbing proliferation of “interpretations,” an astonishing upheaval of words. But for probably all audiences The Silence signified a freedom to see that precipitated the immense transformation of cinema in the 1960s and, in subsequent decades, a vast, global investment in expanding and perfecting image technologies (cf. Koskinen 2010: 43-66). Yet The Silence remains unsurpassed in its synthesis of pantomimic action and cinematic seeing. Although Bergman deployed adventurous pantomimic sequences in later films such as Persona (1966), Hour of the Wolf (1968), and Cries and Whispers (1972), he himself never again relied so much on pantomimic action to construct a film narrative as he did in The Silence nor was his pantomimic imagination quite as inventive or complex. His focus shifted more toward exposing the destructive or repressive powers of speech than toward revealing the cryptic varieties of voiceless bodily communication. As Bergman indicated, in the postwar era, the capacity to construct cine-pantomimic narratives of such seductive seriousness depends on a peculiar condition of being “uninhibited,” of feeling on the threshold of a freedom to see the stories that bodily physical actions tell, and it is just incredibly difficult to possess that lack of inhibition or even the circumstances that enable one to possess it.

Bergman’s highly imaginative use of pantomime in The Silence owed nothing to a Swedish tradition of pantomime in the theater, for pantomime had a negligible presence in Swedish theater long before and well after the making of the film. It is true that he found much inspiration from the distinctive silent films that Sweden made when he was a boy, especially works directed by Victor Sjöström (1879-1960) and Mauritz Stiller (1883-1928), as well as from German expressionist films directed by F.W. Murnau (1888-1931). But Swedish silent films achieved international distinction in part because of the sophistication with which they applied a verisimilar mode of acting, and this in itself was a break with a traditional (histrionic) mode of acting associated with the stage. Bergman further credited two films by Czech director Gustav Machaty (1901-1963) with deepening his attraction to film narratives “without dialogue”: Ecstasy (1933) and Nocturno (1934), both of which contained almost no speech but complex music and noise soundtracks (Bergman 1994: 291). These films urged Bergman to write and direct a largely pantomimic episode (No. 2) in his anthology film Secrets of Woman (1952), and he included powerful pantomimic scenes in subsequent films, such as Sawdust and Tinsel (1953) and The Virgin Spring (1960). Bergman linked pantomime with inventive film performance, with a way to expand the expressive power of film. Pantomime was “traditional” for him only insofar as he disclosed a pattern of fascination with it in film since boyhood. Despite, however, many years as a major, distinguished director of stage plays, Bergman never showed an interest in pantomime for the theater. He depended on cinematic devices to construct pantomimic performance: editing, expressionist cinematography, close ups, mobile camera. As a director for the theater, he worked almost entirely with dramatic texts by other authors, and these authors avoided pantomime. For Bergman, pantomime signified a radical break with the Swedish “tradition” of a voice-dominated dramatic theater, and he never seems to have considered making such a break, perhaps believing that voiceless performance in the theater belonged more appropriately to the prestigious Royal Swedish Ballet. If Sweden had anything resembling a tradition of pantomime before Bergman, it lay with the Royal Ballet, which between 1786 and 1871 staged or hosted numerous “pantomime-ballets,” “historical pantomimes,” and “pantomime idlylls” in a French style, choreographed by ballet masters: Jean-Rémy Marcadet (1755-?), Louis Deland (1772-1823), Jean-Baptiste Brulo (1746-?), Anders Selinder (1806-1874), August Bournonville (1805-1879) (cf. Klemming 1879: 497-506). By 1871, though, the Ballet had sufficiently “freed” itself from pantomime to dispense altogether with using the word to describe anything it produced. As discussed earlier, Jean Börlin staged his very innovative pantomime El Greco with Rolf de Maré’s Swedish Ballet in Paris in 1920, but he referred to it as a “mimed drama” to diminish association with the somehow less appealing term “pantomime.” Bergman himself never used the term “pantomime” to describe his attraction to scenes “without dialogue” in film, perhaps because during his lifetime the word had become too narrowly defined. More precisely, it had come to mean what ballet wanted it to mean: a codified, stylized way of regulating bodily gesture to support ballet narratives whose artificiality supposedly allowed dance to transcend them. It was a French attitude toward pantomime that assumed a performer could not justify voiceless performance without having experienced a rigorous education or training with teachers in a school that sufficiently respected the stylized code (“tradition”) regulating bodily signification whereby, for the most part, the body created an artificial, abstract world of imaginary objects rather than interacted with a world of material objects. Such a narrow definition of pantomime could account for why Bergman preferred to speak of cinematic scenes “without dialogue” rather than explain how pantomime migrated across performance media instead of remaining imprisoned within a definition of it imposed by theater institutions determined to control it severely if not suppress it altogether.

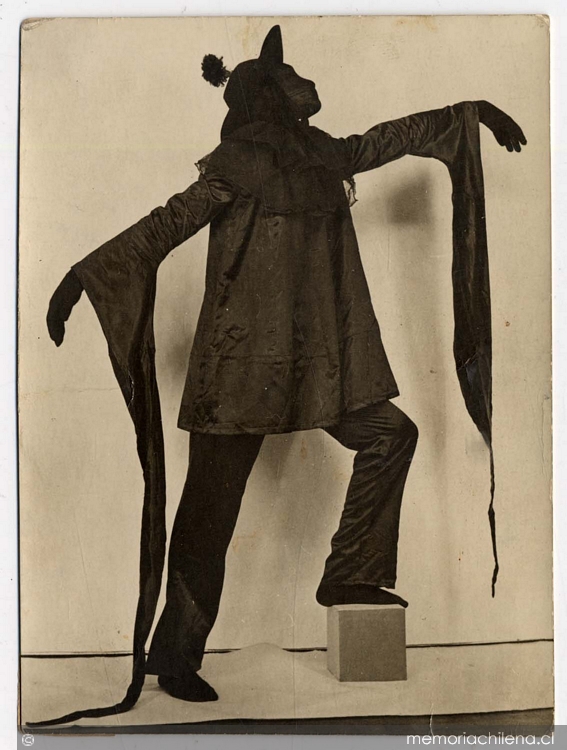

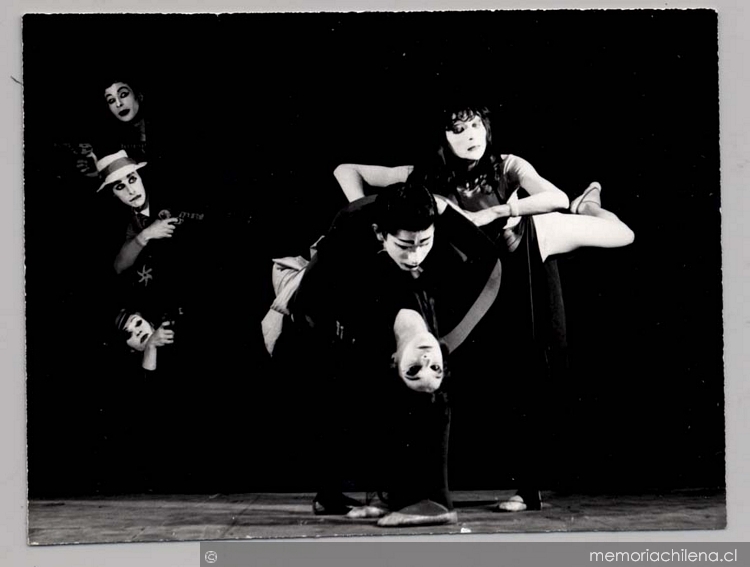

Film Still Series B: Ingmar Bergman’s The Silence (1963). Film technology allowed Bergman to produce unprecedentedly imaginative pantomimic performance. His use of the face to construct character and narrative is well known, but the face was never so free of speech as in The Silence (1-6). But in this film Bergman also made dramatic use of hands to create a remarkable and unstable relation between bodies or even between characters and their own bodies (9-13, 15, 21). The film builds much drama out of the performance of simple, yet intensely observed pantomimic actions, such as walking through corridors, reading, typing, combing, washing, smoking, drinking, comforting, serving or sharing food, or looking out windows (5, 7-8, 11, 16-18, 20, 22, 24, 28). However, the great dramatic power of these actions does not diminish the “shock” effect of other, equally “simple” actions, such as Ester’s masturbation, Anna’s horror at witnessing a couple copulate in the theater, the dwarves putting a dress on Johan, and Anna’s sexual rendezvous in a hotel room with a nameless stranger she encountered in a café (14, 25-27). Yet Bergman did not rely entirely on close ups of fragmented pantomimic actions to amplify their dramatic allure; he amplifies numerous “simple” actions by having them performed within complex, precisely detailed scenic contexts that evoke persuasively a country in which the characters do not understand the language of its citizens (19, 21-23), including mirror reflections (19-20). Actors; Ingrid Thulin as Ester, Gunnel Lindblom as Anna, Jörgen Lindström as Johan, Håkan Jahnberg as the hotel servant, Birger Malmsten as Anna’s sexual partner, the dwarves: the Eduardinis. Photos: Bergman (2003).